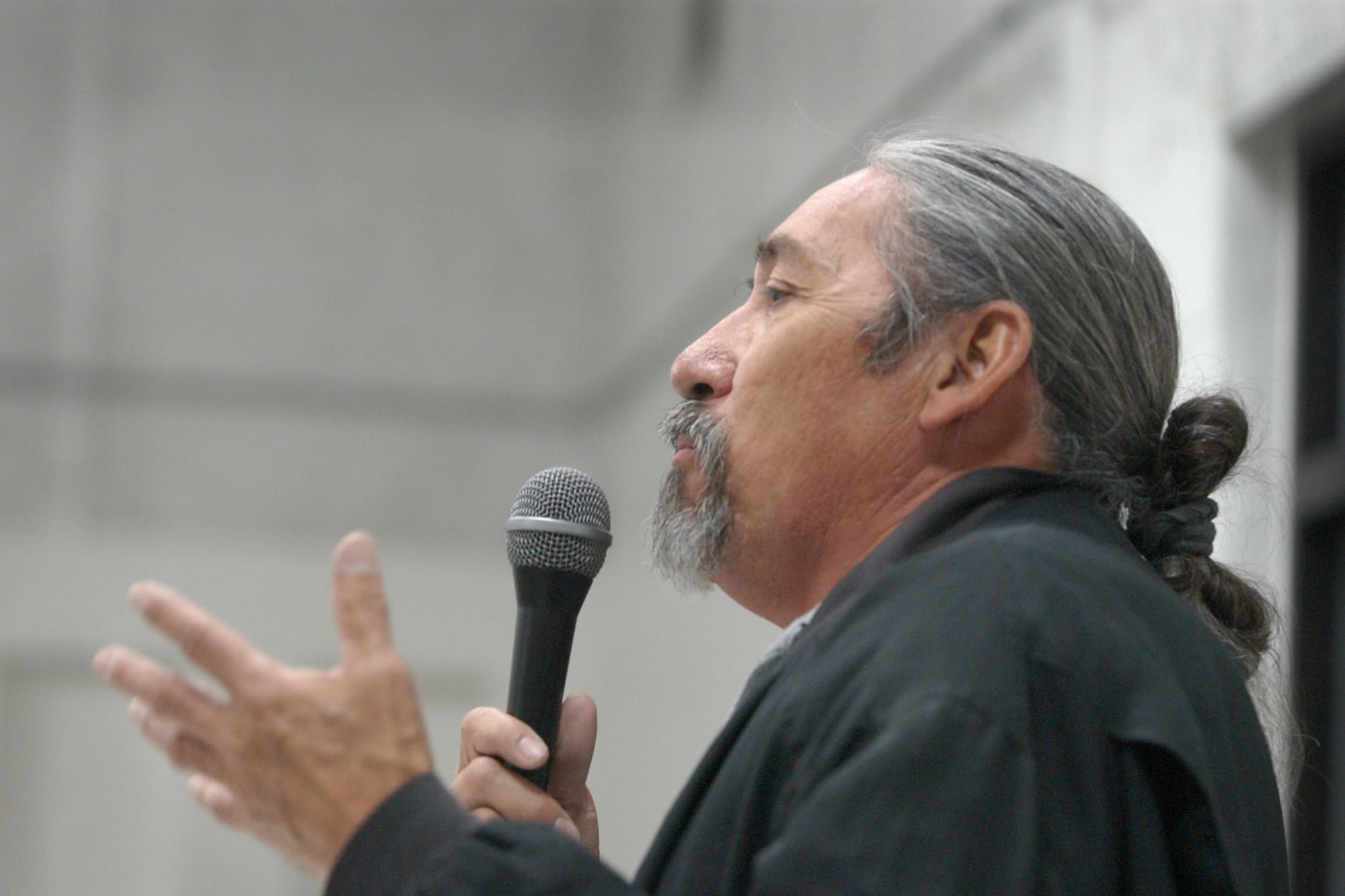

For three decades, Ricardo Martinez, co-founder of the advocacy group Padres & Jóvenes Unidos, helped parents and students fight racism in Denver Public Schools.

Last week, Denver lost the humble and fierce organizer. He died of a stroke and its complications, according to a written remembrance shared by his family.

“At his core, he was a warrior,” said his wife, Pam Martinez, the organization’s co-founder. “At his core, he unquestionably believed in the basic democratic rights of all people.”

The organization helped parents and students take on issues ranging from discipline reform to biased school principals. Martinez was also active on the state and national levels on education and fighting for immigrant rights.

Though much of his work was focused on the Chicano and Mexican communities, his wife said he applied that same gentleness, commitment, and passion “for all oppressed peoples.”

Ricardo Martinez, 69, retired in 2019 from Padres & Jóvenes Unidos, which recently changed its name but retains a similar mission.

“He didn’t just fight for Latino students,” said Denver City Clerk Paul López, who first met Martinez in his youth. “He fought for every student, for everybody’s access to an equal education, regardless of where you were from or what language you spoke.”

Martinez grew up in Southern California, the son of farmworkers, said Pam Martinez. When he was old enough, he worked alongside them in the fields and canneries. As teenagers, Martinez and his sister would take the bus from town to town delivering newspapers put out by the United Farm Workers union and the political party La Raza Unida.

Martinez eventually joined both the union and the party, and became active in the anti-war movement, she said. The Martinezes met on a picket line and moved to Denver in 1982 as young parents. About a decade later, when Ricardo Martinez was working as a labor union organizer, they got a call from parents at Denver’s Valverde Elementary about a principal who was punishing students for speaking Spanish.

The Martinezes helped the parents successfully push for changes at the school. At a celebration of the parents’ victory, Pam Martinez recalled, one Valverde father suggested they keep the organization going — and what was then called Padres Unidos was born.

Over the next 30 years, the organization pressed Denver Public Schools on important issues from preserving bilingual education and improving the quality of school lunches to reducing suspensions and expulsions, which disproportionately affect Black and Latino students.

Padres & Jóvenes Unidos was instrumental in opening a bilingual Montessori elementary school in northwest Denver, Academia Ana Marie Sandoval, and in bringing about reforms at other city schools, including North High School and the former Cole Middle School.

A 2008 overhaul of Denver Public Schools’ discipline policy to reduce suspensions, expulsions, and police referrals was largely the result of years of organizing by Padres & Jóvenes Unidos, which worked with the district to shape the reforms.

“They were bulldogs, and they were not going to let that go,” said Theresa Peña, who was president of the school board at the time. “Where there was compromise, they got 85% of what they brought to the table because they were right.”

Alex Sánchez worked for Denver Public Schools and now runs an advocacy organization, Voces Unidas de las Montañas, in Glenwood Springs. He remembers Martinez as a tireless advocate who was “one of the best in terms of movement building.”

“I have a vivid memory of being at a table with Ricardo when he was challenging the school district when a principal suspended several students because they were wearing a Mexican flag,” Sánchez said. “Ricardo, parents, and youth came to the table and demanded accountability, as they should have, of that principal and the school system.”

Although the Martinezes led the organization, it was always their approach to empower parents and students to speak for themselves, observers said.

“A true organizer isn’t in the front chasing cameras or headlines,” López said. “A true organizer gets behind and pushes. … And he did that.”

U.S. Sen. Michael Bennet, superintendent of Denver Public Schools from 2005 to 2008, said Martinez forever changed the way the city serves its children of color by always making sure students and families were at the forefront of the movement.

“They organized, rallied, and took to the podium to demand justice and academic opportunity,” Bennet said in a statement. “They forged lasting changes in Denver’s neighborhoods and schools. And through their many accomplishments, Ricardo’s legacy will endure.”

Pam Martinez said it was his love for justice and empowering others that drove his work.

“He loved watching people get their consciousness,” she said. “He loved people overcoming fear and turning it into strength and power. He loved seeing the whole community become alive.”