In a split vote, the Denver school board approved a controversial proposal late Thursday that will limit some schools’ autonomy in an effort to shore up teacher job protections.

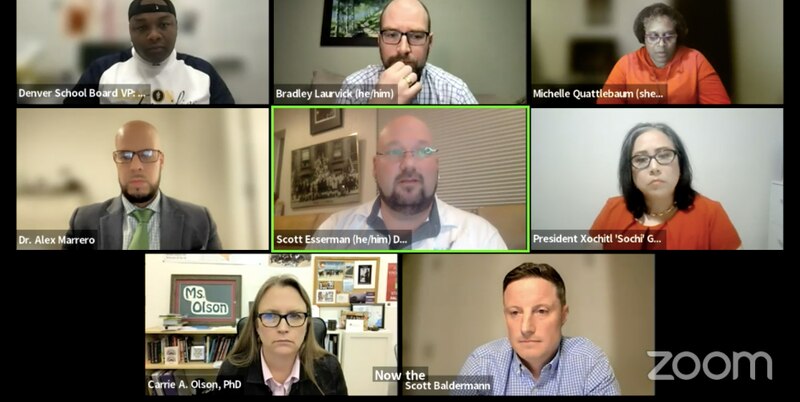

The contentious 5-2 vote came after five hours of public testimony and eight weeks of fierce debate that divided the Denver Public Schools community. It was the board’s first major policy decision after candidates opposed to previous reforms and backed by the teachers union swept all open seats, and it comes as the district and union are negotiating their next contract.

Denver’s 52 semi-autonomous innovation schools will be the most affected by the new policy. Many innovation school principals, teachers, and parents were vehemently opposed to it, arguing that a loss of autonomy would inhibit their schools’ programming and harm students. Innovation schools are run by the district but can waive certain district policies, as well as teacher tenure protections in state law and parts of the union contract.

The new policy will curtail some innovation waivers by requiring all Denver schools, with the exception of those facing state sanctions for low test scores, to:

- Follow the teachers union contract, which guarantees a duty-free lunch, a maximum class size of 35 students, an arbitrator to settle grievances, and more.

- Abide by the state law that grants teachers Colorado’s version of tenure, known as non-probationary status. Teachers with non-probationary status have job protections if they are laid off and the right to due process if they are fired.

In a discussion that was more heated than usual, board members focused more on the process that led to the policy than the policy itself, which is known as an executive limitation because it directs the superintendent. Several board members criticized the process as rushed and flawed, with one calling it “ambush governance.” Ultimately, only board member Michelle Quattlebaum and Vice President Tay Anderson voted against the policy.

“There should be no surprises,” Quattlebaum said. “And there were surprises.”

Board President Xóchitl “Sochi” Gaytán co-wrote the proposal with member Scott Baldermann, who introduced it at a board meeting in January. Neither the teachers union, which supported the proposal, nor the innovation leaders who opposed it, said they knew it was coming.

Baldermann and Gaytán’s original proposal was more sweeping than the one approved Thursday, with provisions requiring a standardized school calendar, a 40-hour work week, a ban on busywork, teacher salaries that ranked in the top three in the region, and more.

Pushback from the innovation school community was strong — and it continued even after the board agreed to simplify the proposal and remove some of the provisions that had proven most unpopular, such as the standardized school calendar.

Students, parents, teachers, and principals from at least 11 of the 52 innovation schools spent hours asking the board not to pass the proposal, which some called secretive, irresponsible, and oppressive. They said their schools serve students well and treat teachers fairly, even without the contract protections, and questioned what problem the board was trying to solve.

“Why try to fix what isn’t broken, and why in such a rush?” said Mandy Martinez, a teacher at Escuela Valdez, a dual language innovation elementary school.

A smaller number of teachers implored the board to pass the policy. Christina Medina, a union member and teacher at McGlone Academy, an innovation school that serves preschool through eighth grade, said the Denver Classroom Teachers Association supports innovation.

“What we don’t support is stripping workers [of] rights,” she said.

Before voting no, Anderson moved to postpone the vote until June. Board members Quattlebaum, Carrie Olson, and Scott Esserman spoke in favor of postponement in the hopes that the board could use the extra time to work with both sides to come up with a compromise.

But Gaytán argued that 60 days was sufficient for the community to weigh in. She referenced a survey in which a majority of teachers who responded supported the changes. Superintendent Alex Marrero noted that the board had gathered “an immense amount of feedback.” Board member Brad Laurvick said postponing would prolong the controversy.

Anderson’s motion to postpone failed after he changed his mind and voted against it, saying he was tired of being gaslit. Esserman and Olson, who initially spoke in favor of postponement, ultimately voted for the policy along with Gaytán, Baldermann, and Laurvick.

“I don’t think we need to sacrifice teacher rights as a means for innovation,” Laurvick said.

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.