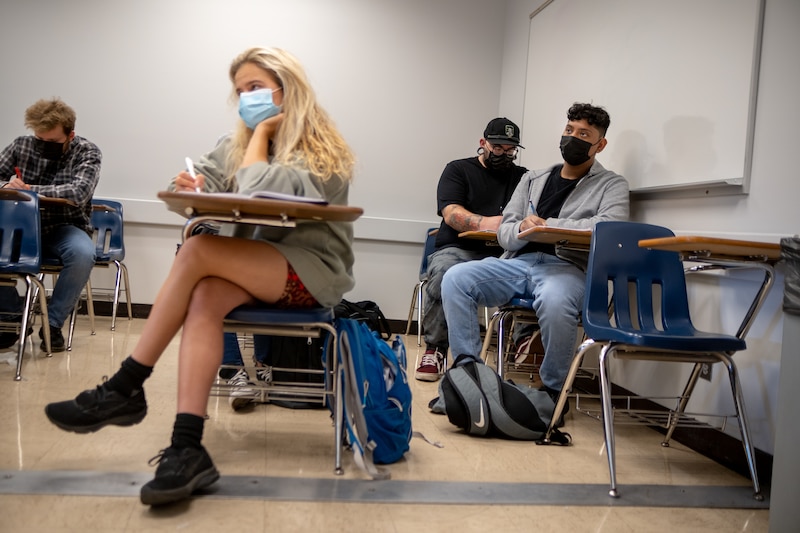

Colorado is a highly educated state but doesn’t send enough of its own high school graduates to college. And fewer students of color and those from rural communities hold advanced degrees.

Chalkbeat Colorado launched its higher education coverage in 2020. Building off our reporting, we want to host a conversation about the “two Colorados.” What are the barriers preventing students, especially students of color or those from rural backgrounds, from getting to and through higher education? What do students and educators want to see change? What are the success stories that Colorado can learn from?

During a May 17 discussion hosted by Chalkbeat Colorado and Young Invincibles, students, experts, and educators will speak about their suggestions for bettering access to Colorado higher education. Read on for Chalkbeat’s reading list for event attendees and anyone who wants to better understand how these issues are playing out in Colorado schools and beyond.

We hope you find these compiled stories helpful. Do you have any remaining questions? Or story ideas for us? Reach out at co.tips@chalkbeat.org. And want to stay up-to-date on all of the most important higher education news? Sign up for our Beyond High School newsletter.

Rural Colorado students go to college at low rates. One tiny school goes against the trend.

Fewer than half of rural Colorado’s high school graduates go to college, a rate that’s about five percentage points below the state average.

The reasons are complex. College can feel far away, geographically and culturally. Colleges sometimes haven’t done enough to make degrees feel relevant to the interests and experiences of rural Coloradans. The cost can deter students unsure if college will improve their earnings. College recruiters don’t often stop at rural high schools.

Tiny Fowler, with its lone high school of about 110 students, shows how rural communities can use a partnership among educators, parents, and the broader community to foster the idea that college degrees will contribute to success — whether graduates return to Fowler or move to a bigger city.

Two Hispanic brothers wanted to go to college in Colorado. Here’s why only one made it.

Jimy and Luis Hernandez are two brothers who both aspired to attend college one day. Only one of them pursued higher education after high school. The brothers’ divergent paths highlight how Colorado’s, and the nation’s, college system produces unequal results — even within the same family.

And even if they do get to campus, Hispanic men may find not many people share their experiences and understand their challenges. Fewer than one in 10 tenured professors are Hispanic, which is important in making students feel welcome and in helping them connect with mentors who can guide them.

Colorado graduates Hispanic men at low rates — but it can improve

Hispanic men go to college at the lowest rates of any student group in Colorado, and all the factors that make it hard for them to get to campus — tight budgets, family obligations, unclear pathways, and few mentors — follow them through college.

These outcomes are not inevitable. Around the country, a few institutions have nearly eliminated these gaps by developing systems that catch students before they stumble, rewarding professors for doing more to connect with students, and creating communities that embrace students on campus. The efforts start with a clear message from leaders that this work is a priority and not an afterthought or an extra.

A Denver scholarship foundation wanted to know how to help Hispanic men get to college. Here’s what it found

What barriers do Hispanic men face getting to and graduating from college?

That’s the question Denver Scholarship Foundation leaders asked Hispanic men about their challenges. They variously listed a lack of funds, information, support, and individual attention, plus family responsibilities.

Hispanic men who did graduate reported having family support. Or they decided to continue with college despite the costs, and had teachers or mentors who saw their potential. They benefited from encouragement from an early age.

How Colorado could get more students to complete FAFSA

FAFSA opens up the possibility for students to gain scholarships and federal grants to pay for the cost of college, and every year Colorado students leave about $30 million in federal financial aid unclaimed. A report by 20 experts calls for nearly doubling the FAFSA completion rate to 80%, from 45% — or to at least move into the top 10% of all states in the measure.

The report recommends the state offer grants for student aid counselors, beef up marketing to spread the message about the benefits of FAFSA, partner with organizations to help students complete the FAFSA, incorporate FAFSA into student academic plans, and eventually add FAFSA completion as a graduation requirement.

Colorado lawmakers took up some of these recommendations in House Bill 1366, which passed with bipartisan support. The bill calls for online tools to make filling out the financial aid form easier and ensures students know about the financial aid form as part of their individualized career and academic plan.

Caroline Bauman connects Chalkbeat journalists with our readers as the community engagement manager and previously reported at Chalkbeat Tennessee. Connect with Caroline at cbauman@chalkbeat.org.