When Jude Keener-Ruscha realized the lockdown Thursday at Denver’s Northfield High School wasn’t a drill, they looked at the two good friends sitting next to them.

“I thought, ‘Well, if I die sitting next to these two people, then it’s not that bad,’” said Jude, who will be a senior next year. “And that’s a thought no student should have in a classroom.”

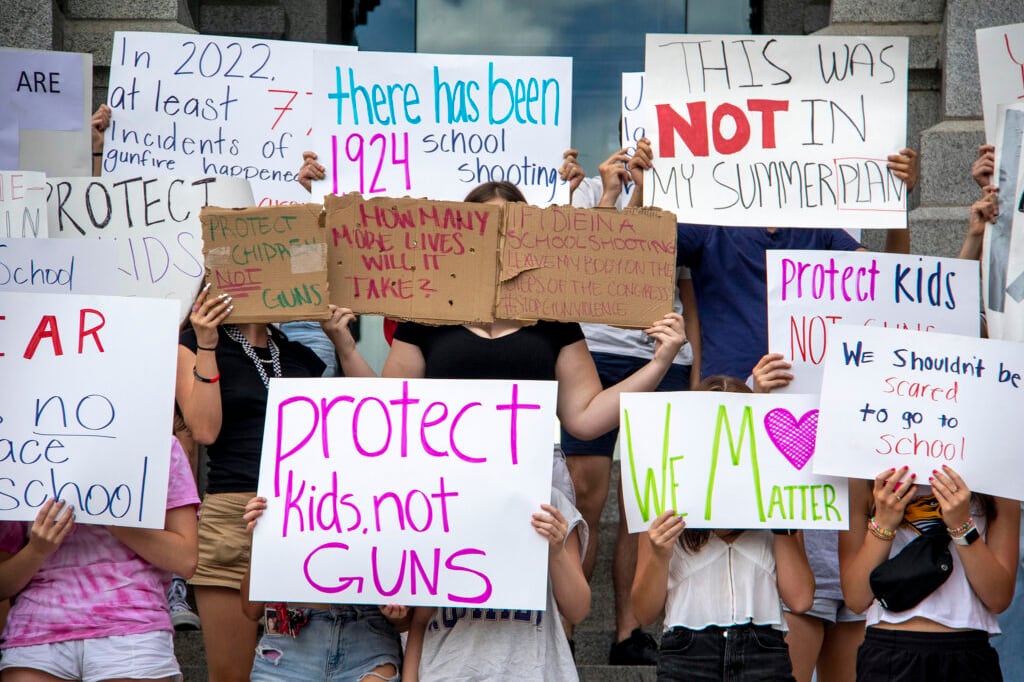

Jude was among about 75 Denver Public Schools students who rallied on the steps of the Colorado Capitol building Friday to call for gun control and an end to school shootings. The rally took place one day after the lockdown at Northfield High, three days after a gunman killed 19 students and two teachers at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, and four years after Denver students held a similar rally after a deadly school shooting in Parkland, Florida.

“Nothing has changed,” said Elliot Guinness, who helped organize a Parkland remembrance event in 2018 and graduated from Northfield Sunday. “I feel hopeless. I feel like there’s no room for growth in this country because our leaders, they don’t seem to listen.”

Northfield High went into lockdown Thursday because of a report of a gun on campus. It turned out to be a paintball gun. Two boys were detained by police, interviewed, and released to their parents, the Denver Police Department said on Twitter.

But the students who huddled in darkened classrooms for more than an hour, trying to remain quiet, said they didn’t know the reason they’d been ordered to hide. It was Northfield’s last day of school, and many students said they quickly realized it wasn’t a drill.

Alee Reed, a rising junior, hid in the back of a chemistry classroom. Her phone blew up with Snapchat and Instagram messages conveying rumors about what was going on.

“Rumors spread like wildfire: ‘There’s a guy with a gun. There’s snipers on the roof. It was just a senior prank,’” Alee recalled. “There was a moment when the WiFi shut down and we got nothing. No texts, no chats, no updates. Everything went silent, and that left me feeling alone.

“People often say ignorance is bliss,” Alee continued. “But if the ignorance is whether or not your friend texted you back that they’re alive, it is in no way bliss.”

Zach Holsinger was in the hallway talking to a teacher when the lockdown announcement came over the loudspeakers. Other teachers called for Zach to come hide in their classrooms, but Zach panicked and ran out a nearby exit.

“It felt like a horror movie,” said Zach, a rising junior. “I see my friends running, and crying, out of the school. I don’t feel like I should go to a school where people are running for their lives.”

After the lockdown was lifted, students were bused to a reunification center, where they waited for hours as school officials checked parents’ identification before releasing their children.

“Seeing my parents’ face, I never want to make them think I might not leave school again,” said rising junior Margaret Freeman. “After what happened in Texas, it felt so much more real.”

Authorities emphasized that no one was hurt at Northfield, but rising senior Hola Maka said, “that doesn’t say anything to the mental and emotional distress that a lot of students experienced.”

The students at the rally called for stricter gun control and said they don’t want their younger siblings and cousins to grow up in a world where lockdowns are a normal part of school.

“We deserve to feel safe at school,” said rising junior Anna Sandene. “This is us speaking out.”

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.