Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

Wednesday was a big day in Inmaculada Martín Hernández’s class. The students in her college-level conversational Spanish class at Denver’s North High School were conducting a Model United Nations presentation, and their teacher sensed they were nervous.

So after Martín Hernández went over the objective for the day, but before the students paired off to strategize, she led them in an exercise called finger breathing.

Gripping her right thumb with her left hand, she instructed the students to do the same.

“Inhale,” she told the students in Spanish. “Hold. Exhale.”

She repeated the exercise for all 10 fingers.

Quick mindfulness breaks are a staple in Martín Hernández’s class. They are also part of a growing number of strategies, including free virtual and in-person therapy, to address student mental health needs that were amplified by the pandemic. The finger breathing lesson is courtesy of a Denver-based nonprofit organization called Upstream Education that provides bite-sized well-being lessons for middle and high school students.

North High was one of the first schools to use Upstream, which is now in more than 40 Denver public schools, according to Upstream Executive Director Tessa Zimmerman.

After seeing Upstream in action, school district leaders decided to spend just under $60,000 in federal pandemic relief to partly fund that expansion, said Bernard McCune, the executive director of extended learning, athletics, and activities for Denver Public Schools. The Caring for Denver Foundation, funded with voter-approved tax dollars, is also backing the expansion.

“You can’t leave a school that’s doing Upstream and not be impressed,” McCune said.

Zimmerman started Upstream because she herself had anxiety as a child and panic attacks at school. That changed when she got a scholarship to a private high school where the principal led the students in mindfulness activities every day during homeroom.

Those activities changed her life, Zimmerman said. “I changed from a student who hated going to school to a student who loved to go to school,” she said.

When Zimmerman was in college, she realized the inequity of her experience: She had access to mindfulness activities at her private school, but many other students did not.

So Zimmerman came up with an idea for a social and emotional learning curriculum for teenagers, and in 2016, entered a design contest run by the DPS Imaginarium, the district’s former in-house innovation lab, which the district dissolved in 2019 due to budget cuts. Zimmerman won $9,000 from DPS that helped her start Upstream.

For the past seven years, the organization has refined its tools with the help of students, including a 10-student task force that Upstream pays during the summer to review a couple dozen of its lessons with an eye to making them more relevant. Teachers have provided feedback, too.

“We found from teachers that they really wanted to do this work, but if they had a 30-minute lesson, it was not feasible,” Zimmerman said.

So Upstream made all of its lessons 10 minutes or less. The finger breathing lesson clocks in at 4 ½ minutes. Another lesson meant to teach students to show themselves grace is 7 ½ minutes. In it, students briefly write down a challenging moment they had recently and then listen as their teacher reads phrases like “I am not alone” and “I can restart my day over at any time.”

The lesson plan includes a script for what teachers should say next: “You can recite these phrases to yourself in the middle of class or during a performance — whenever you need some reassurance or a moment of self-compassion.”

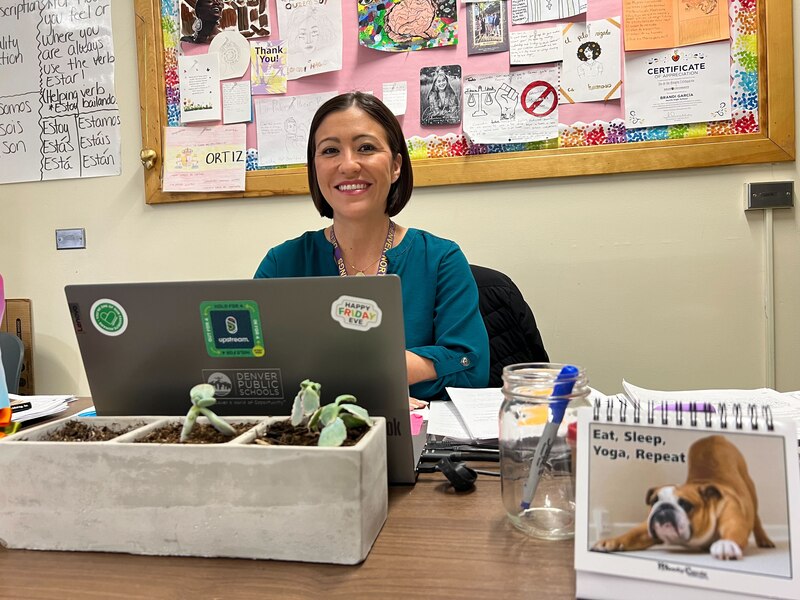

North High teacher Brandi Garcia started using Upstream in 2020 during remote learning and continued using the tools when students came back to her classroom in person. She said she loves that they are “super easy to follow. It’s plug and play.”

After students do an Upstream exercise, Garcia said, “they feel a lot lighter.” She’s noticed that even students who are resistant at first eventually come around.

“There’s some kids that are like, ‘Oh, I don’t want to do this,’” she said. “Then before you know it, they’re right there with the breathing. Then they’re like, ‘Are we going to breathe today?’”

North High social worker Maria Hite uses Upstream with students in her therapeutic groups and in her one-on-one sessions. Posters with Upstream techniques hang in her office, which features soft lighting, a box of fidget toys, and a mini Zen garden with a rake.

On Wednesday, Zimmerman handed Hite a stack of square stickers. The stickers, which were an idea from Upstream’s student task force, have a bumpy texture and instructions for how to do the “box breathing” exercise, which involves tracing a finger around the edge of the square and breathing in for four seconds on one side and out for four seconds on another.

Hite revealed her own box breathing hack: She has students flip their cell phones screen-down and trace their phones with their finger.

“A lot of my time is spent working with students who are anxious,” Hite said. “If you can show a tool that works really quickly, it’s easier [to get] buy-in.”

Spanish teacher Martín Hernández said she likes that the exercises create “that moment of connection, even when not all the students want to do it.

“But everyone is calm and quiet, and everyone respects it.”

On Wednesday, junior Audrey Gilpin was among the students who took part in the finger breathing exercise. Gilpin said it’s nice to come into Martín Hernández’s classroom from the chaotic hallway of the 1,600-student high school and take a few minutes to pause. It’s a small respite that several students said improves their own mental health and helps them feel more comfortable in class.

“It makes me feel like my teacher cares about how I feel mentally,” Gilpin said.

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.