Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

Monarch Montessori has a plot of land picked out for the middle school it hopes to build: a field of tall native grasses, located just past the yurt where it holds music classes and a short walk from its outdoor solar oven and chicken pen.

But Denver Public Schools Superintendent Alex Marrero is recommending that the school board reject Monarch’s application to add sixth, seventh, and eighth grades when it votes this week. Marrero said the charter school’s plan to pay for and build a new middle school wasn’t good enough.

“This is not in spite of the advocacy,” Marrero told the board last Thursday. “It’s based on our lived and hard-earned experience when it comes to granting expansion without a clear facility plan. We’ve been burnt in the past, quite frankly. It just simply doesn’t work.”

Marrero’s recommendation likely reflects the changing realities for publicly funded, independently run charter schools in Denver. Ten years ago, DPS was the fastest-growing district in the state and its board was keen to open new charter schools it deemed promising. Now, both of those trends have reversed. Enrollment in DPS is declining and the board has been closing charters, not opening them.

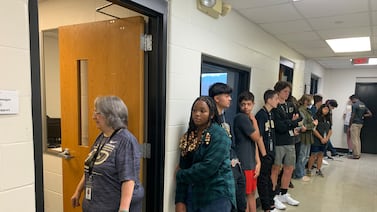

Monarch offers a bilingual Montessori education unlike anything else in far northeast Denver. It became a charter school in 2012, adding elementary grades to what had been a private Montessori child care center. The school board initially rejected Monarch’s charter application, a decision Monarch appealed to the Colorado State Board of Education. The state board sided with Monarch and ordered the Denver board to vote again.

Monarch serves about 280 elementary students this year. Its demographics closely mirror the district’s as a whole; nearly 60% of students are Latino, 17% are white, and 14% are Black.

Monarch’s proposal calls for the school to add sixth grade in 2027, seventh grade in 2028, and eighth grade in 2029. Parents have been asking the school to expand to give students in a historically underserved part of the city the same opportunity to continue with Montessori as those on the opposite side of Denver, school leaders said

Executive Director Laura Pretty has been pitching the expansion as mutually beneficial to Monarch and DPS; it would fix some historical inequities at the school and address the district’s need for more middle school seats in far northeast Denver, she said.

Monarch is one of five public Montessori elementary schools in Denver and the only one without a sixth grade. That matters because Montessori classrooms are multi-age, and the “upper elementary” classrooms are traditionally a mix of fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-graders.

“Our kids have two pathways right now, which is, after fifth grade, they are wealthy and they get to go to a private school that fosters their independent learning,” parent Christina Williams told the board Thursday, “or they’re not so wealthy and they go to a traditional school, and that has a very different outlook. I am noticing our students are in panic.”

Although enrollment in DPS is declining overall, the far northeast is the one region where the student population is expected to grow because of new housing developments. The district’s enrollment analysis says it will need more middle school seats there by 2029, an issue that board members said even a modest Monarch expansion could help address.

“If there are 30 kids that are staying at Monarch Montessori, those are 30 kids we don’t have to provide seats for,” board member Scott Esserman said.

But the board also seemed receptive to Marrero’s reservations about the expansion. District staff described Monarch’s expansion timeline as “too compressed” and dinged the school for not yet having the loan to pay for it, according to a presentation given to the board.

Pretty said Monarch faces a Catch-22. The school can’t get financing from its lender until the district approves the expansion, which is estimated to cost between $6.5 and $7 million, she said. And the district won’t give the approval without the financing.

“It’s like saying you can’t start school until you’ve graduated,” Pretty said. “To me, the argument for us is very strong and the arguments the district is making against it, I feel, are incredibly weak.”

Several board members implied that it would be a tough decision. The board is set to vote on Monarch’s proposed expansion at its next meeting Thursday.

“I stand behind the idea of a strong dual language Montessori school,” board President Carrie Olson said. “And I’ve learned from the years on the board that opening schools without a good plan leads to closure later, and that’s heartbreaking for the families.”

Melanie Asmar is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Colorado. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.