A few months ago, four top federal education officials got an internal memo from a prominent civil rights group, The Education Trust, offering a roadmap for shrinking the role of police in schools.

The document lays out a vision for a shift in civil rights enforcement, complete with a candid accounting of potential pitfalls. Most notably, it calls on the Biden administration to warn that the presence of police in certain schools, and police involvement in routine discipline, could violate students’ civil rights.

“The Biden administration must counter this dangerous narrative that more police, weapons, and surveillance in schools will help keep schools safe if it wishes to make true improvements to school climate nationwide,” it said.

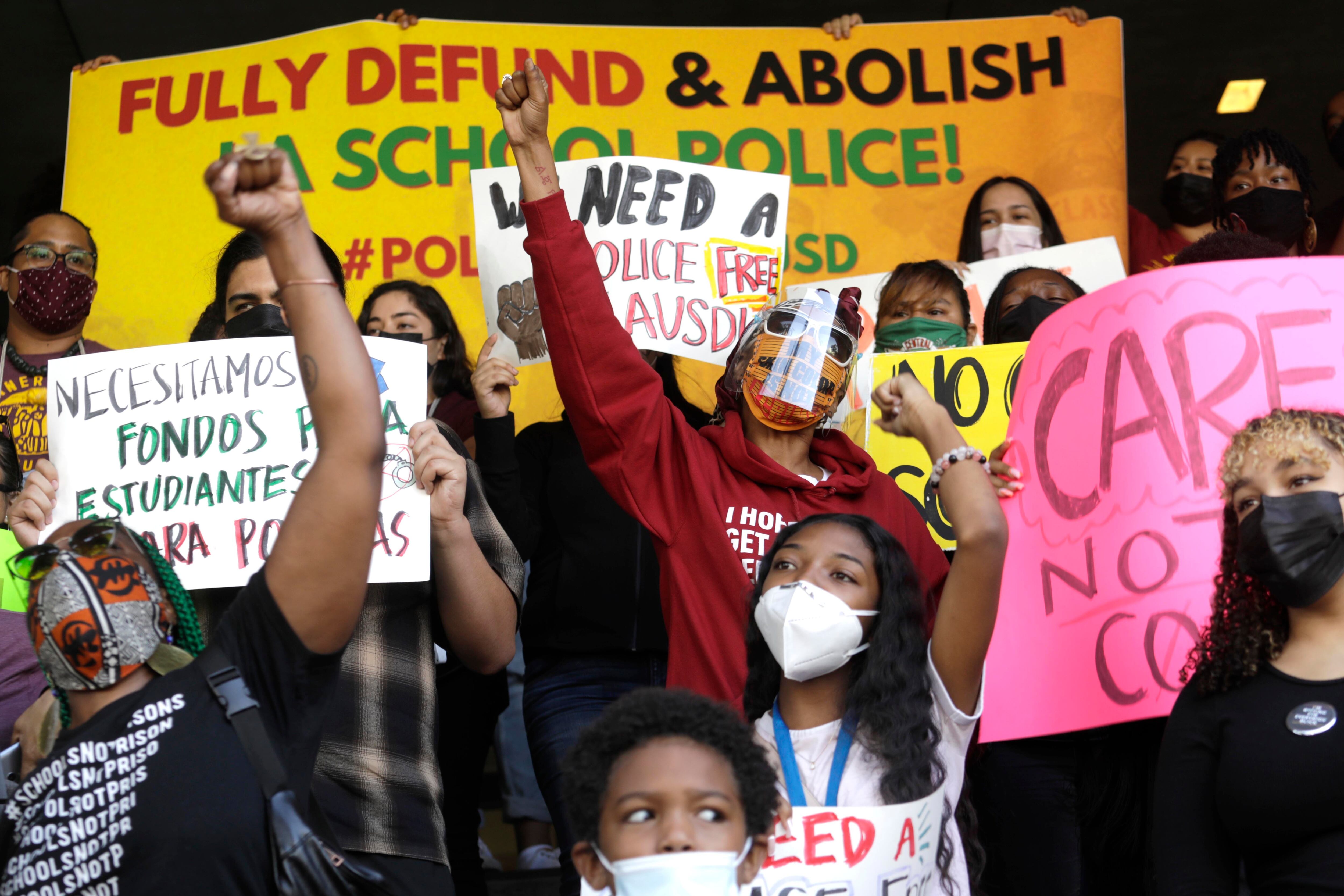

The memo offers a window into the pressures the Biden administration is already facing on an issue that has roiled many school districts since George Floyd’s murder — what role, if any, police should play in schools. Federal education officials have signaled that they plan to examine the department’s guidance on discipline and police in schools. Civil rights groups are preparing to weigh in, though any changes to school policing are likely to be met with intense pushback.

The Biden administration “might shy away from it, because it is a hot-button issue,” said Dan Losen of UCLA’s The Civil Rights Project, referring to school policing. “But I think it’s a serious issue. The time has come. It’s overdue. It would be hard for them to be totally silent on it.”

A spokesperson for the department did not respond to questions about the memo, including whether education officials have relied on it. Earlier this month, the U.S. Department of Education asked for feedback from the public about school discipline and discrimination, including how students interact with school police.

“What we’ve heard thus far from the Department of Education has been very encouraging,” said The Education Trust’s Courtney Bollig. “It’s clear that they understand the importance and the urgency of this issue.”

The federal government’s role in school discipline has been a live issue since 2014, when the Obama administration released guidance pushing schools to avoid suspensions and expulsions. When students of color received a disproportionate share of such punishment, officials warned, that could violate civil rights law. The guidance also encouraged school districts to develop formal written agreements with police that spell out officers’ roles.

There is some dispute about how much of a difference the guidance actually made, with one survey finding that few district leaders changed their policies in response.

Regardless, in late 2018 the Trump administration revoked it, arguing that it had made schools less safe. Officials at the time connected the guidance to the school shooting in Parkland, Florida, though there was little if any evidence to support the tie.

Biden has promised to step up civil rights enforcement, and his education department’s call for public comment is seen as a precursor of potential policy change, including new guidance. (Biden’s nominee to lead the department’s Office for Civil Rights, Catherine Lhamon, helped issue the 2014 guidance when she served in the same role under Obama.)

“We know that students of color are often disproportionately impacted by disciplinary actions,” a Department of Education spokesperson said. “That is why the Department is working to engage a variety of stakeholders on this issue to ensure all students feel safe at their schools.”

Some civil rights groups say reducing the presence of police in schools must be part of that agenda. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, a number of school districts weighed scrapping school police — a number ultimately did, while many others kept them.

“What we hope to see specifically around policing in the new guidance is a clear statement that school policing is harmful to students,” said Katherine Dunn, a program director at Advancement Project, a nonprofit that has advocated to remove police from schools. “This guidance needs to signal to districts that they need to end the use of policing.”

The memo to department officials — created by The Education Trust and the nonprofit National Women’s Law Center — makes a similar case, though it doesn’t go as far as stating that police should be removed completely from schools.

Instead, the groups say the federal government should discourage police from routinely interacting with students, and discourage schools from putting police in schools that serve higher numbers of students of color, especially Black and Native American students. They want federal education officials to say those actions could constitute a federal civil rights violation.

The memo, obtained by Chalkbeat through a public records request, was sent to four department officials, including Ian Rosenblum, who used to lead The Education Trust’s New York chapter.

Realizing these civil rights’ groups goals won’t be easy, though, especially because some school officials, teachers, and students are skeptical about limiting police in schools.

Surveys have found that many students feel safer with police present, but Black students are much less likely than other students to feel this way. Research shows that police officers in schools generally lead to more suspensions and arrests, particularly for students of color, and in some cases, declines in academic performance. But some research, including a recent North Carolina paper, has found that police reduce serious violence in schools.

“There’s one thing everyone seems to agree on,” said Lucy Sorensen, author of the North Carolina study and a professor at the University at Albany. “It’s not good for [police] to be getting involved in minor disciplinary matters.”

While Education Secretary Miguel Cardona has pushed to reduce suspensions and expulsions for students of color, it’s unclear if he would support sweeping efforts to remove police from schools.

“When trained well, when working in partnership with the school to be proactive and a support for students, it’s a positive thing,” he said in May. “I’ve seen models where it works exceptionally well, where it even provides a pathway for students to look at themselves as potential law enforcement officers.”

In Philadelphia, 18-year-old Sheyla Street has had police officers stationed in her schools since she was in fifth grade. Alongside other Black students, she helped lead efforts to reform discipline in her school and citywide.

She’s seen a range of officers: Some have made efforts to connect with students, while others were intimidating. She remembers watching a police officer bang handcuffs on the desk in front of her sixth-grade class when he was looking into a cyberbullying incident — “That was aggressive,” she said — and as a high schooler, a police officer checked her bag each morning as she went through a metal detector at the school’s entrance.

“I wouldn’t say it’s a great way to start your morning off,” she said. “It seems unnecessary.” She’d like to see the federal government push schools to redirect money spent on school police to counselors and mental health support for students.

Other powerful groups may oppose efforts to curtail school police, the memo acknowledges. While national teachers unions have expressed support for school discipline reforms in the past, local unions have sometimes opposed them or protested plans to cut ties with police. The memo also points to AASA, the school superintendents’ association, as a potential opponent.

“They’re correct in saying that we don’t support additional federal guidance,” said Sasha Pudelski, AASA’s advocacy director. “I would have thought that the civil rights community would have seen that the previous guidance did not have much of an impact and not be so invested in having another set of guidance.”

Perhaps a bigger hurdle will be conservatives, many of whom have already rallied against campaigns to “defund the police” at a national level. The issue could be even more fraught now, as a backlash to efforts to address racism in schools continues to gain steam.

“We should be pretty worried about this fall,” said Michael Petrilli, president of the Fordham Institute, a conservative education think tank. “You’ve got all these kids who have been traumatized. Some kids are going to externalize that behavior — they’re going to act out when they get back to school.” More counselors could help, he said, but even still, limits on school police could disrupt school or endanger students and staff.

Others counter that police should not be the ones dealing with student trauma due to the pandemic.

“It’s important to not just talk about taking police out of schools, but also what are we replacing them with?” said Adaku Onyeka-Crawford, director of educational equity at National Women’s Law Center. “How are we adding more adults in the building who are trained to meet the needs of students — replacing the school-based police officer with a nurse, with a counselor, with a mental health professional.”