Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

When immigration agents raided a fast-fashion warehouse a mile from Santee Education Complex in Los Angeles earlier this month, the tension in the school was palpable.

That did not let up after a student learned his father and grandfather had been detained in that day’s raids. Staff consoled the student as he waited to be picked up, making sure his family knew about resources that could be helpful to them.

As the 1,600-student school readied for graduation day, principal Violeta Ruiz responded to worried messages from her students over Instagram and recorded voice messages assuring families it was safe to attend the upcoming ceremony.

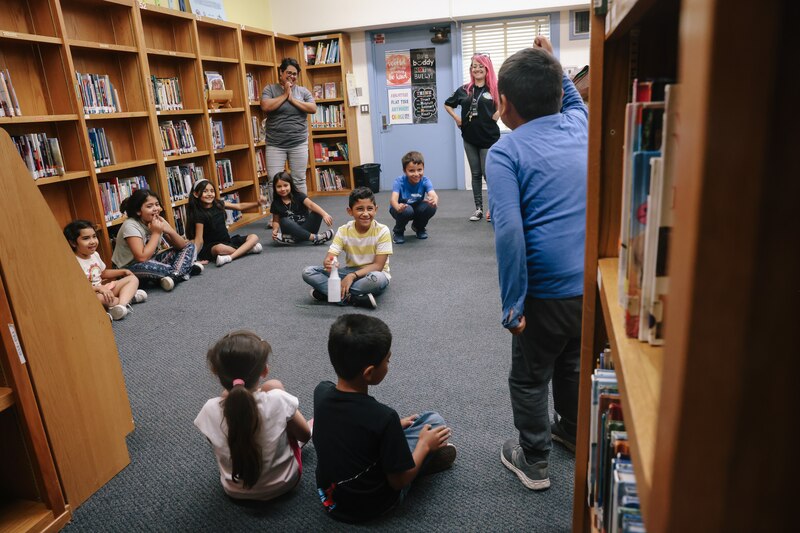

And when summer programming started Tuesday, Ruiz made sure students saw her familiar face as they arrived, even though she’s technically not on the summer school staff.

“I made sure to be out because the kids all know who I am,” Ruiz said. “Some of them were a little uneasy, but as soon as they entered our gates, they were ready to go.”

Ruiz’s experience illustrates what schools at the epicenter of President Donald Trump’s mass deportation campaign have had to do to counteract the fear rippling through their communities. Schools like Santee, where 1 in 5 students are English learners, are spending time and money to keep kids in school and tend to families in crisis. Los Angeles Unified added 100 summer school sites after the raids to cut down on the amount of time children and parents spend in transit, where they might cross paths with an immigration agent.

The stakes are high: Recent research from Stanford University found that immigration raids in California have contributed to an already alarming absenteeism crisis.

What’s playing out in L.A. also underscores why it’s so important for school leaders across the country to stay in contact with families this summer, said Alejandra Vázquez Baur, director of the National Newcomer Network, a coalition that works to support new immigrant students.

Many school communities are feeling the effects of heightened immigration enforcement, she noted, from Charlotte, North Carolina, where a parent was detained not far from the school dropoff line, to New York City, where a high schooler was detained at a routine immigration hearing.

“It is especially important now for school leaders to step up and speak out on this issue, communicate with families, and share what they are doing differently to ensure that schools are being protected in the next week and beyond,” Vázquez Baur said. “These are the experiences that will impact the attitudes of families as they consider whether they will return in the fall.”

The worst-case scenario, she said, would be if parents took stock of the situation this summer and decided: “It is too risky for us to send you back.”

Why summer is key time to connect with immigrant families

On the first day of Trump’s presidency, federal officials revoked a longstanding policy that treated schools, churches, hospitals, and other places that provide critical services as “sensitive” locations where immigration enforcement was limited. Since then, there haven’t been raids on schools, but enforcement carried out nearby has left many school communities shaken.

In L.A. for example, the recent raids began as Los Angeles Unified was preparing to host hundreds of graduation and moving-up ceremonies for students. The district stationed extra school police outside some events and scrambled to set up Zoom feeds for families too afraid to attend. Some parents whose children were the first in their family to graduate from high school didn’t get to witness that milestone in person.

At a press conference held Tuesday at Santee, Los Angeles Unified Superintendent Alberto Carvalho said he hoped the additional summer school offerings would show immigrant families that the district is committed to supporting them.

In addition to expanding summer school sites from 220 to 320, Carvalho said the district would offer transportation to any child whose family requested it, again to cut down on the time parents spend in transit. Kids too afraid to attend in person would also be given the option of virtual summer school.

“We will allocate the resources to do everything we can to stabilize and normalize your condition, despite the challenges that you’re facing,” Carvalho said.

It is not yet clear how much the summer school expansion will cost, Carvalho said. That will depend on how many students show up at the new sites and how many additional staffers are needed. The district’s summer school operation was already a sprawling endeavor with some 90,000 students enrolled in traditional academic-focused programs, and another 40,000 involved in enrichment activities, such as math or swim camp.

“This is an action without precedent in this school district, but it is again, the right investment at the right time for absolutely the right kids,” Carvalho said.

While it’s important for schools not to over-promise what safeguards they can provide, Vázquez Baur said, schools can make clear to families this summer what their policies are if an immigration agent shows up on school grounds, and what resources they can offer if a student or family member is detained off campus.

School principals can ensure that new hires get the proper training on how to interact with federal immigration officials, and invite trusted community organizations to attend summer events to put families at ease. Schools can also review and update their protocols, especially if they notice new immigration enforcement tactics over the summer.

Above all, she said, it’s important for schools to maintain regular communication with families. If there was a weekly email during the school year, keep that up, Vázquez Baur said. And if immigration enforcement is affecting the broader school community over the summer, it’s important to acknowledge that, too.

“This is not a break from the school year communication,” she said. “When families don’t know, there’s even more fear.”

For Ruiz, Santee’s principal, keeping students and families in the loop has been a key way to maintain trust.

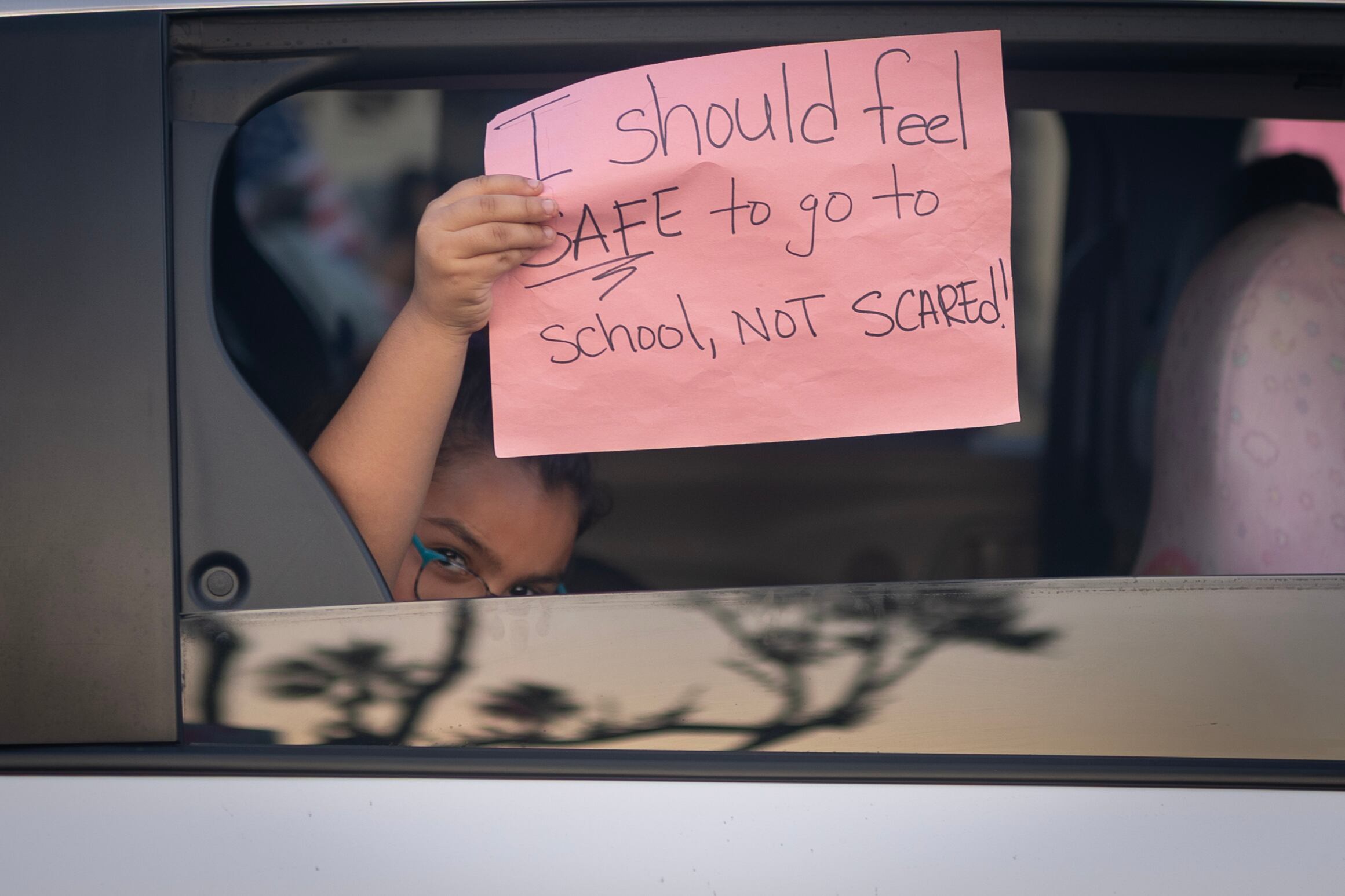

In February, for example, when immigration agents first swept through Los Angeles, some of Ruiz’s high schoolers started walking out of school in protest.

After talking it over with students and staff, the school decided to host an assembly to give students a safe emotional outlet. Teens put on skits about what they’d do if they were stopped by an agent and how to support one another if someone they loved got detained. They taught each other to be allies, and how to defend themselves, Ruiz said.

In the weeks that followed, Ruiz met with parents to make sure they understood what the school would do if immigration enforcement happened near campus. Students got “red cards” listing their constitutional rights. Some teachers hung butterflies on their classroom doors made by the school’s MEChA student group to show support for undocumented students.

And after a few staffers made butterfly T-shirts to wear at school, lots of staff and students started showing up in their own butterfly attire.

To Ruiz, it was an unspoken but unmistakable way to tell students: We are here for you.

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.