Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

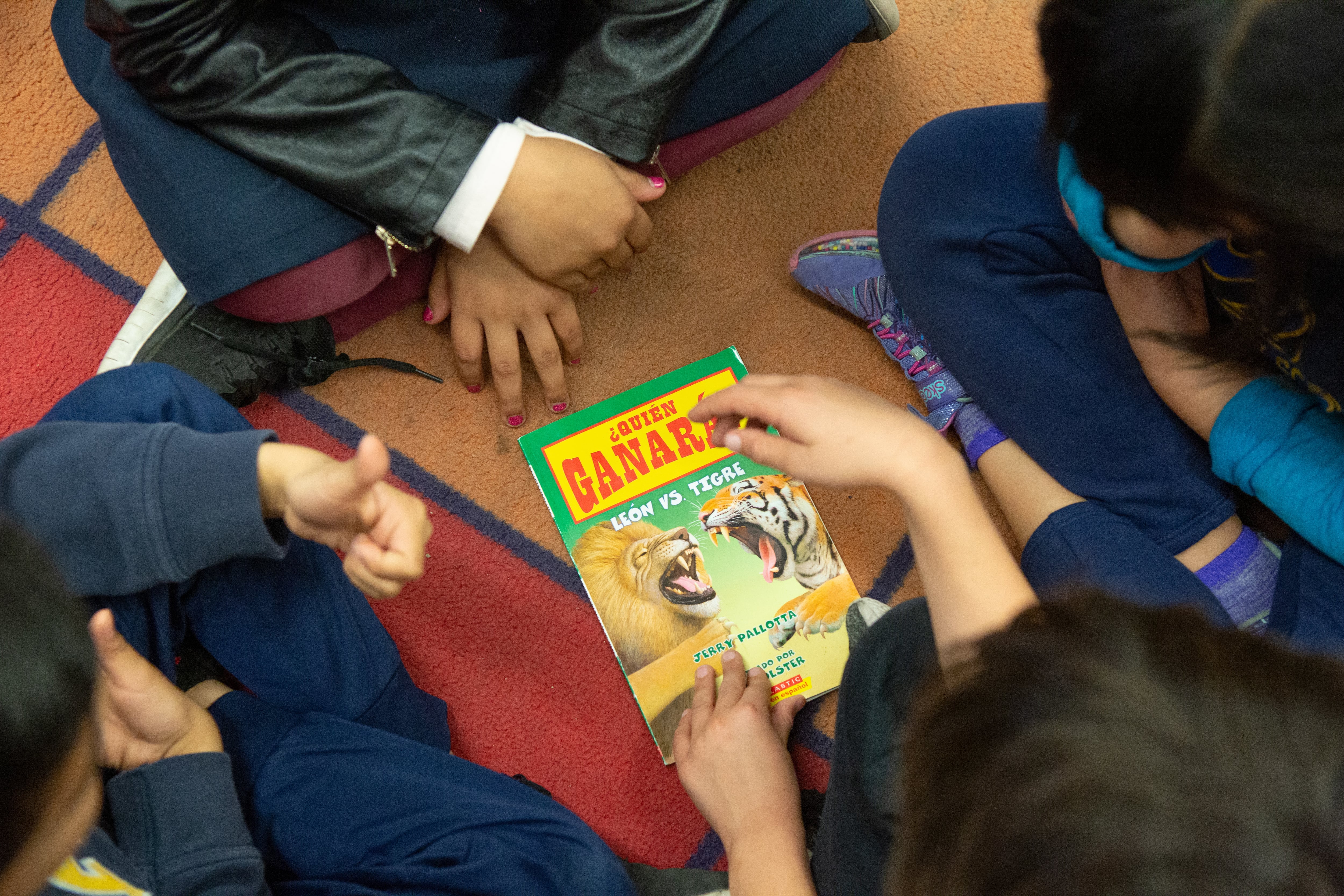

The Trump administration has quietly rescinded guidance spelling out the educational rights of the nation’s more than 5 million English learners that educators say was crucial to serving children from immigrant families.

In recent weeks, a Dear Colleague letter issued in 2015 by the Education Department and Department of Justice was stamped with a red message saying the document had been formally rescinded. Neither agency issued a public notice explaining the rationale for the change as they usually do when they roll back federal guidance.

The rescission comes after the Trump administration laid off nearly every staffer in the Education Department responsible for serving English learners and looks to wind down a federal website that provides toolkits for helping English learners. The administration has also proposed zeroing out dedicated Title III funding for English learners and issued an executive order declaring English the official language of the United States.

Trump officials also cleared the way for immigration agents to make arrests at or near schools, child care centers, and after-school programs, undoing a longstanding precedent to treat those places as sensitive locations. The administration’s mass deportation campaign has left many school communities shaken and lowered student attendance in some parts of the country.

Unlike students with disabilities, whose rights are clearly spelled out in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the rights of English learners stem from multiple Supreme Court cases and federal laws that prohibit discrimination based on national origin, which courts have interpreted to mean schools must take steps to help children overcome language barriers so they can obtain a meaningful education.

The 40-page Dear Colleague letter was groundbreaking when it was released under former President Barack Obama and remained a critical resource, according to educators who relied on the guidance. It gathered various case law, legal precedents, and federal requirements regarding English learners in the same place and provided clear examples about how students should be served.

Rescinding the guidance doesn’t change those laws, but advocates for English learners worry it will now be harder for schools to know if they are complying with the law and to hold schools accountable when they are not.

“A lot of people are very worried at the state and district level,” said Montserrat Garibay, the advocacy chair for the National Association for Bilingual Education. Without clear guidance, “there’s a high risk that EL students are not going to be receiving their linguistic and their academic support that they need.”

Garibay, the former director of the Office of English Language Acquisition during the Biden administration, likened the guidance to a “bible” for educators who work with students learning English. Her organization is hosting a training next month to help schools navigate its loss.

Garibay said she used to print out the 40-page guidance document when she was a teachers union leader in Texas and use it to train teachers. She knew teachers who would highlight the pages and bring it to their principal to ensure they assessed English learners properly and provided families with documents in their native language.

An Education Department spokesperson told Chalkbeat on Tuesday that the department had rescinded the guidance “because it is not aligned with Administration priorities” but did not respond to followup questions about what exactly was out of alignment.

A Justice Department spokesperson said the agency had no comment on Wednesday.

But the agency referred the Washington Post to a July memo from Attorney General Pam Bondi sent to all federal agencies offering guidance to comply with Trump’s order that English be the official language.

That memo says the Justice Department would rescind any guidance that interprets the federal ban on national original discrimination to require language services for people who aren’t proficient in English. It also said the agency would “lead a coordinated effort to minimize non-essential multilingual services” and “redirect resources toward English-language education and assimilation.”

The 2015 guidance document says that schools must, to the extent practicable, translate certain notices for parents into a language they can understand and provide free oral translation when a written translation isn’t possible.

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.