Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

Two years after the Supreme Court ended affirmative action as America knew it, the decision has become the cornerstone of the Trump administration’s legal argument against nearly any effort to promote diversity in education.

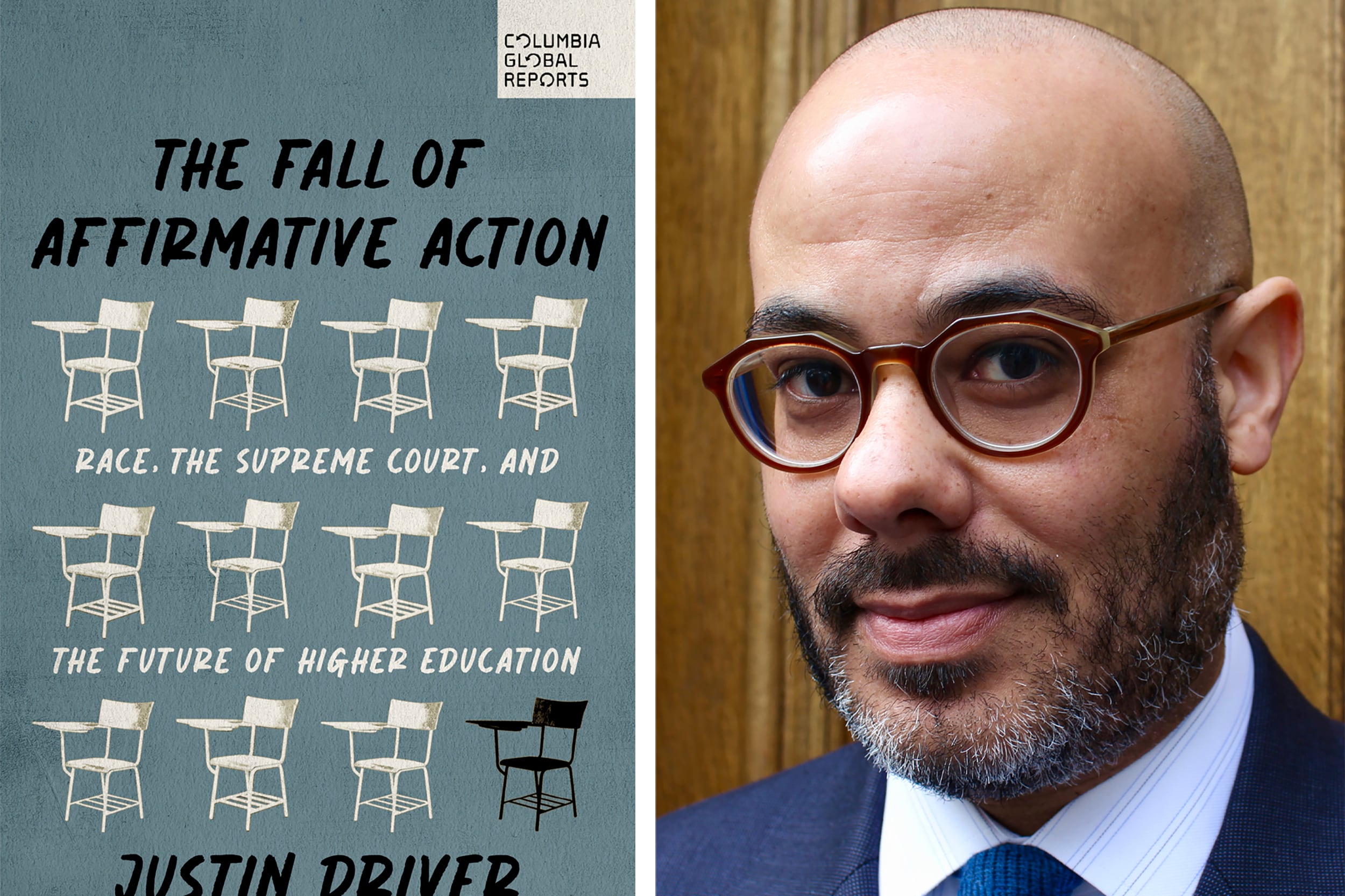

In a new book, legal scholar Justin Driver tries to set the record straight about what Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard does and does not mean.

Checking off a box to indicate your race? No. Looking at an applicant’s name or photo to guess their race? Also no.

But giving admissions preferences to the descendants of slaves, immigrants, enrolled tribal members, or kids who come from disadvantaged schools and neighborhoods? That’s all fair game in Driver’s book, “The Fall of Affirmative Action.”

“A major reason that uncertainty engulfs the SFFA decision is the Trump administration’s efforts to distort what the decision actually means,” said Driver, a professor at Yale Law School. “The Trump administration has contended that universities are prohibited from taking steps to improve racial diversity on campus, even when they do not use express racial classifications of individual students. That’s not something that SFFA v. Harvard forbids.”

Trump administration officials have said the ruling applies to K-12 schools, not just colleges, and that it extends beyond admissions to hiring, scholarships, prizes, support for students, discipline, graduation ceremonies, and “all other aspects of student, academic, and campus life.”

A federal judge blocked the administration from applying that interpretation. But the head of the Justice Department recently issued similar guidance stating that racially neutral strategies, such as considering a child’s ZIP code, are unlawful proxies if they’re used to boost racial diversity. (Even before SFFA, K-12 schools could not consider the race of an individual child for the purposes of school desegregation, but courts have permitted that kind of geographic targeting.)

Education Secretary Linda McMahon told colleges last month they now have to report the race of all applicants and admitted students, along with grades and test scores, to prove they aren’t using racial preferences. The administration has also sought to bar universities from using any “identity-based preferences” and opened an investigation into a selective Virginia high school over its admissions policies, even after the Supreme Court let them stand.

All of that has the very real effect of confusing kids of color who aspire to attend highly selective colleges, Driver writes. He points to the experience of Demar Goodman, a Black student from Atlanta who set his sights on attending Harvard. After the Students for Fair Admissions decision, the teen decided it wasn’t worth applying. And he changed the topic of his personal essay from how he overcame the challenges of attending an underfunded school to why he collects flag pins.

Since the ruling, Black and Hispanic enrollment has fallen at many top colleges, as has the share who are admitted.

“Universities, in my view, should investigate every constitutionally permissible means that they can use to make sure that they do not have a paucity of Black and brown students,” Driver said. “This nation is confronting grave problems today. Too many Black students at fancy colleges is not among them.”

Chalkbeat spoke with Driver about how the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia would view today’s affirmative action debates, the parallels between the Students for Fair Admissions decision and a major ruling on K-12 desegregation efforts, and why colleges shouldn’t give up on diversifying their student bodies.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

You draw attention to how jurists like Antonin Scalia have explicitly said that if a program just happens to benefit Black students, but its goal is actually to lift up low-income or disadvantaged kids, they don’t have a problem with that. Why do you think those arguments have gotten lost in the conversations we’re having now about what constitutes an ‘illegal proxy’ for race?

Justice Scalia is not my favorite justice of all time, but he is, in my estimation, the most influential justice of the last five decades. President Trump has said he wishes to appoint justices in the mold of Scalia. One of the things that I’m attempting to do is to remind people of this passage from this major figure in American constitutional thought [that] has been overlooked from his days as a law professor.

He can be understood to be fleshing out what Chief Justice Roberts’ SFFA opinion says: What’s forbidden is race qua race, race for the sake of race. Justice Scalia says, when he’s writing decades earlier: If universities are attempting to court students from, say, low-income backgrounds, if those students who benefit end up all being Black, that is constitutionally permissible, because it’s not treating people with race qua race.

The Trump administration says if universities decide to get rid of, say, standardized testing with an eye toward increasing racial diversity, that’s forbidden. Justice Scalia has written things that vehemently disagree with that.

What do you think the legacy of SFFA is so far for the K-12 level?

I found it quite noteworthy that in the wake of SFFA, the Supreme Court declined to hear a lawsuit involving Thomas Jefferson High School in northern Virginia. It seems to me that was an indication that the Supreme Court did not want to get further enmeshed in this business of race and admissions anytime soon.

I do think that one way to understand SFFA is that it brings the court’s jurisprudence involving higher education and what we might call lower education into harmony. The Parents Involved case from 2007 can be understood as also now applying to higher education.

The Parents Involved opinion was really a fight about the legacy of Brown v. Board of Education. Louisville and Seattle did, in some instances, take account of the race of individual students with an eye toward promoting racial integration. Because if you simply assign students to the local schools, the persistence of residential segregation would prevent the schools from reflecting the diversity of the areas. The Supreme Court invalidated that measure.

But Justice Kennedy, writing the controlling opinion, says that while racially classifying individual students is forbidden, nothing prohibits school districts from drawing district boundaries with an eye toward promoting integration, nothing prohibits them from deciding where to build a school within a city with an eye toward promoting racial integration. Justice Kennedy expressly says color blindness is not required in all instances.

And that’s where we are with respect to SFFA v. Harvard, which says that students can write essays about their encounters with racial discrimination. And there are other approaches that would court students from low-income backgrounds that would not violate the Constitution of the United States. That’s an underappreciated aspect of this decision.

Some think, in this political moment, colleges should just keep their heads down, not draw attention to themselves with new policies that aim to diversify their student bodies. You say you think that that’s a mistake. Why is that?

I get that college administrators are in a very difficult position. The Trump administration is being difficult.

However, these institutions have a responsibility to stand up for their core principles and should not permit a misinterpretation of a Supreme Court opinion to mandate the composition of their student bodies. That is fundamentally a matter of university autonomy and academic freedom.

Just because the Trump administration wishes that the SFFA decision went further than it did, that does not succeed in making the Trump administration’s vision the law of the land.

We are in the midst of seeing — or perhaps more accurately, not seeing — a lost generation of Black students on elite college campuses. The consequences of that decline are going to be felt throughout American society for generations to come. What starts on college campuses doesn’t remain there.

Universities have an entire panoply of options that are open to them that do not violate the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. At universities that have suffered these staggering declines in Black enrollment, we should understand those declines for what they are: a choice.

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.