Last January, before COVID-19 hit, the Denver school board and superintendent took a personality test. The test, discussed in public at a retreat, was meant to help the board members and superintendent understand each other so they could work better together.

The results showed several board members had dominant personalities, not an uncommon trait for decision-makers. Superintendent Susana Cordova, then halfway into what would end up being a two-year stint as district leader, got a different personality type: a patient collaborator who doesn’t like to offend others.

Those traits held true throughout Cordova’s tenure as superintendent, as she strived to increase cooperation and lead through a series of acrimonious and unprecedented challenges. They are also evident when she talks about why she is leaving the district after a 31-year career. Her supporters, though not Cordova herself, have blamed the school board for pushing her out.

“It’s really important for the board to feel 100% aligned with their superintendent,” Cordova, 54, said in an interview. “It’s important for the board to be able to spend the time, the energy, and the focus on the development of their strategy with their superintendent, and to have a superintendent that they trust to do this work and that they will put all of their weight behind.”

Was that not the case when she was superintendent?

Cordova is diplomatic.

“The absence of an articulated approach and plan makes it hard for everybody,” she said.

Cordova’s last day is Dec. 31. She’s headed to Texas, where she will work as a deputy superintendent in the Dallas Independent School District.

Denver school board members have said that dealing with the immediate crisis of the pandemic stymied efforts to develop a long-term plan. Absent one, they said they’ve led with their values, passing resolutions to remove school police officers, reopen comprehensive high schools in communities of color, and move away from judging schools based on test scores.

Cordova said her overarching goals were aligned with the board. When she became superintendent in January 2019, one of her priorities was “to break historic patterns of inequity so all students can thrive, not by accident but by design.” For example, she spoke about improving education for Black and Hispanic students by starting with recognizing their excellence. Two months into her tenure, the school board passed a Black excellence resolution.

“There was not a ton of sunlight between those priorities I had in my superintendency and where the board believes the majority of the work should be,” Cordova said. But, she said, “this board will serve itself well going into the future by truly articulating the goals that it has around what they hope to see for the organization. And in the absence of those goals, it will be really hard for the board and for the future superintendent to be clear on both the ‘what’ and the ‘how.’”

Deep roots

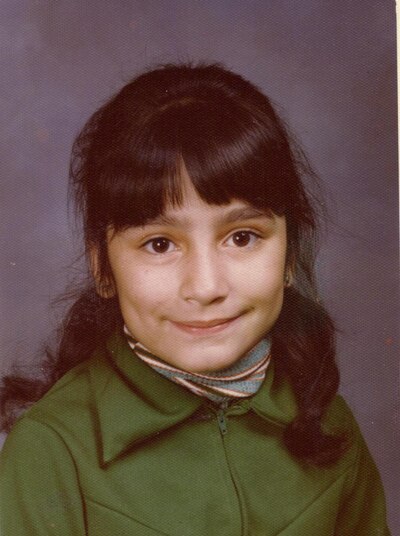

As the child of Mexican-American parents and a graduate of Denver Public Schools, Cordova has firsthand experience with those historic patterns of inequity. She credits her success to the education she received, but has noted that her experience was not universal.

“A lot of the message I heard growing up was that the way to be successful in school is to leave your culture behind and embrace a different culture, a culture of academics. The way to success is to get up and get out,” Cordova told Chalkbeat in 2016.

“I wanted to be the kind of educator who said to kids, ‘You can be successful, you can have choices, and you don’t need to leave your community to do that.’ It’s important for kids of all backgrounds to see [people] who look like them and who are successful.”

Cordova was the first Latina superintendent in a district where more than half of all students are Hispanic. Her appointment was both historic and meaningful.

“Growing up, I didn’t have teachers, school leaders, or central office leaders who looked like me,” said Jesús Rodríguez, a former Denver teacher, principal, and principal supervisor under Cordova. “Let me tell you, it makes quite the difference. Susana being a bilingual, Latina woman who looks like so many of the students and families in Denver was huge.”

That she was literally from Denver mattered, too.

“She’s this young girl from the west side of Denver. She did not go to high-performing schools. Her mother was a school secretary,” said Theresa Peña, a former school board president. “That she could speak about equity from a lived experience changed our conversation as a district.”

Cordova started her teaching career in 1989 as a dual language teacher at the now-closed Horace Mann Middle School. She taught at West High School before becoming principal of Remington Elementary, a high-poverty school that was later shuttered. Cordova helped boost test scores at Remington and also brought professional artists into the school.

She began working in the district’s central office in 2002, where she held a variety of titles over the next 17 years from literacy director to deputy superintendent. She was long an advocate for diversifying the curriculum, expanding access to rigorous college-level courses, and improving instruction for students learning English as a second language.

Denver Public Schools is under a court order to serve English language learners, who make up about a third of all students. In 2012, Cordova took the lead in rewriting the plan. What had historically been an adversarial process was praised by participants as cooperative.

As she plans to leave the district, Cordova counts the academic gains made by Denver’s English language learners among her accomplishments. Denver students regularly outperform English language learners statewide on state math and literacy tests. More than 3,000 Denver graduates have earned a “seal of biliteracy” on their diploma, signifying their fluency in English and at least one other language — a celebration of multilingualism that Cordova championed.

Cordova is also proud of Denver’s improved graduation rate and the rise in students passing college-level courses. She said Denver high school students earned 54,000 college credits last year, saving them and their families a combined $8.7 million in tuition costs.

One of her own fondest memories from high school is when her Advanced Placement European History teacher promised to take any student who passed their AP exam for dinner at a fancy restaurant. Cordova had never been to a fancy restaurant, and she remembers the thrill of eating at The Hungry Farmer on West Alameda Avenue.

“That was so motivational to me,” Cordova said. “I worked really hard on that.”

Making a mark

Cordova was the sole finalist for superintendent, a scenario that made some community members feel like she was anointed rather than hired. The school board was pivoting away from controversial education reform policies, such as closing low-scoring schools. Critics wondered whether Cordova was too tied to the old strategies, which failed to close test score gaps between white students and students of color.

Right away, Cordova got a chance to show how she was different. The teachers union was on the brink of a strike, pushed to the edge by more than a decade of reform policies, including an unpopular pay-for-performance system. Cordova took a different approach to negotiating with the union. Unlike her predecessor, she was at the bargaining table for every session, and she stayed even-keeled as the crowd of teachers chanted, “If they won’t pay us, shut it down!”

The strike ended after three days and an all-night public bargaining session. Cordova pledged to improve what had historically been a tense relationship between the district and the union, inviting union leaders to sit in on high-level meetings and soliciting their feedback.

She also started a teacher advisory council to hear teachers’ thoughts on issues they identified. One night last year, she sat in a school library discussing testing over crudités and cans of bubbly water. She listened to teachers describe their experiences, interjecting to ask technical questions and seek input on how the district could improve its testing regimen.

One of Cordova’s gifts is her ability to relate to other people and make them feel comfortable. On that night, she talked about how, as a young teacher, she got into a car accident and missed a couple of days of school. At the end of the year, she found a stack of paper tests she was supposed to have given students on the days she missed.

“I didn’t know what to do, so I threw them away,” Cordova said. “Isn’t that terrible?”

As she prepares to leave Denver, Cordova said she’s proud to have “changed the tone and tenor of our relationship with our teachers.” She always aimed to stay connected to her teaching roots. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Cordova directed central office employees to work in schools to help alleviate staffing shortages. She made no exception for herself.

Once a week, Cordova headed to Bryant-Webster Dual Language School, where she was once an assistant principal, to help in preschool and first grade classrooms. The highest paid employee in the district did recess duty and kept watch while teachers took bathroom breaks.

“She never forgets where she came from,” former board president Happy Haynes said.

It’s fitting that one of Cordova’s favorite stories from her time in the district is about students making their mark. When Cordova taught at West High School, she used to let students eat lunch in her classroom. One day, a student was sitting in the window well during lunch time and noticed decades of graffiti: teenagers’ names scrawled in pencil on the bricks, going all the way back to the 1930s and protected from the elements by the window eaves.

“It made me feel better that I wasn’t the first teacher who had a kid hanging out the window,” Cordova said. “And it was a fun piece of history. Our schools have served generations and generations and generations of kids. Neighborhoods change, demographics change, but there are some things about kids that just don’t change. That’s what’s so great about school.

“I take a lot of comfort in the idea that kids are kids everywhere, and they desperately need teachers and leaders who believe in them.”