State evaluators have approved the main reading curriculum used in Colorado’s largest school district after initially saying it didn’t pass muster.

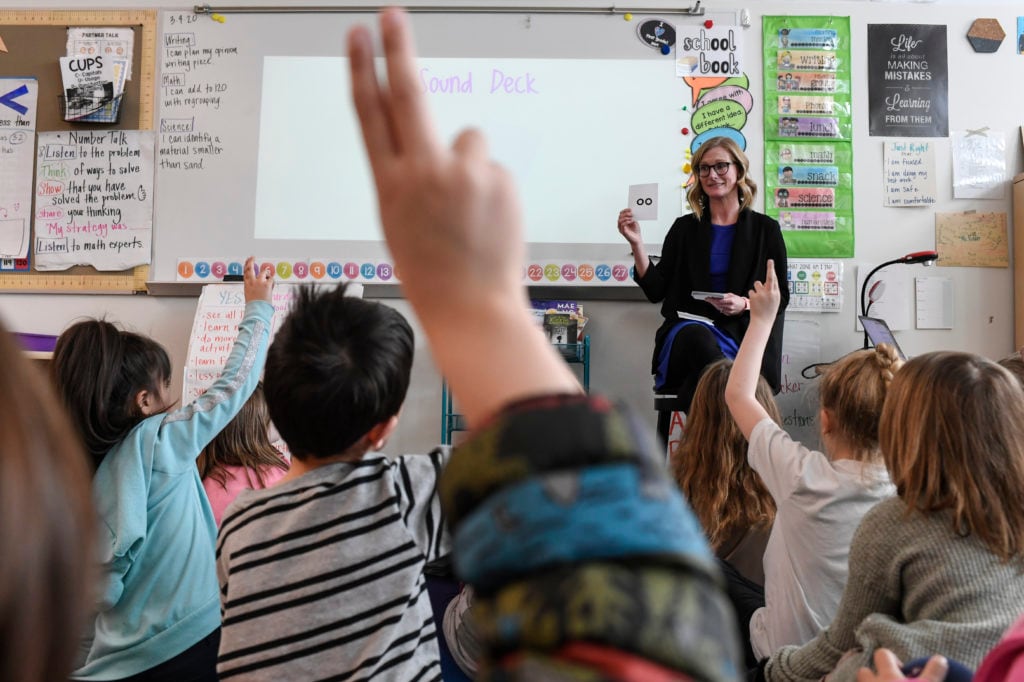

As part of Colorado’s ongoing effort to get more students reading well, state evaluators recently vetted more than 20 reading curriculums used in kindergarten through third grade. In April, they approved eight of them.

But Benchmark Advance, the primary curriculum used in most Denver elementary schools, wasn’t on the list because it didn’t earn a passing score. Two months later, after the curriculum’s publisher, Benchmark Education, made changes to the product and appealed the state’s decision, its score rose enough to make the list for kindergarten through second grade.

With new rules requiring Colorado schools to use reading curriculum backed by science, the state’s list of approved curriculum is a big deal. Districts using programs on the list won’t have to make expensive, time-consuming changes in the midst of a coronavirus-fueled budget crisis. Districts that use curriculum that didn’t make the cut — and lots of districts fall into this category — could face penalties if they don’t switch.

Benchmark Education was the only publisher to revise its core curriculum during Colorado’s review process and the only one to win such a substantial reversal.

A few other curriculums, including EL Education, Core Knowledge Language Arts, and Wonders, got approval after appeal for one or two additional grade levels — but were always on the 2020 approved list in some form. Each curriculum was reviewed originally and on appeal by a team of two to four evaluators, which included Colorado educators and state education department staff.

Eric Hirsch, executive director of EdReports, a national nonprofit that reviews curriculum, said it’s not uncommon for curriculum publishers to make revisions during the review period. Colorado education officials said they didn’t treat Benchmark differently from other publishers that appealed evaluators’ decisions.

“They were not granted a permission different from anyone else,” said Floyd Cobb, the state education department’s executive director of teaching and learning, in an email. “If a vendor has the resources and desire to make changes to their program while it’s under review, that is at their discretion. We will review what they present.”

In their 788-page appeal document, Benchmark officials said the version of the curriculum they initially submitted for review was a 2021 pilot edition and that they made changes in response to evaluators’ critiques in the final version.

The company made a number of revisions across several grade levels. For example, the units now give teachers more guidance on helping students learn and practice vocabulary. Benchmark also revised units so teachers provide immediate feedback when students practice a new phonics skill.

The company’s Spanish-language counterpart — called Benchmark Adelante — was also initially rejected by state evaluators. An appeal of that decision is not yet complete.

Denver district officials described the approval of Benchmark Advance as a good step, and said they’re waiting to see if Benchmark Adelante will be approved on appeal too.

“In our estimation, there is no discernible difference in the components or the quality of the resources” in Advance and Adelante, said Tamara Acevedo, Denver’s deputy superintendent of academics.

The district first adopted Benchmark Advance and Benchmark Adelante five years ago. Neither were approved by the state education department during a 2017 review, but at the time it didn’t matter much since the state had little power to control curriculum choices.

That changed with the passage of a 2019 state law updating a landmark 2012 law called the READ Act. Fed up with stagnant reading proficiency rates despite many millions spent on struggling readers, lawmakers gave state education officials new powers to control curriculum choice, oversee reading-related spending, and mandate teacher training on reading instruction.

The state has not detailed how it will use its new oversight power, especially given the additional financial stress districts are now facing. Denver, for example, has already planned to save money by delaying science curriculum purchases. No doubt, the approval of Benchmark Advance represents one less headache for district leaders in the coming year.

That’s not to say some Denver schools won’t have to make changes. Only about two-thirds use Benchmark Advance or Adelante. The rest use a variety of different curriculums, including several the state judged subpar.

Denver is among five Colorado districts, including Aurora, Cherry Creek, Mesa County Valley, and Mapleton, that use a popular curriculum the state soundly rejected. It’s called Units of Study for Teaching Reading, or known popularly as “Lucy Calkins.” The program, which at times has students guess at words instead of sounding them out, scored so poorly in the state’s first round of evaluation, it didn’t move on to the in-depth secondary evaluation, and failed again on appeal. The same thing happened to a curriculum called Fountas and Pinnell Classroom, which is used in some Denver, Aurora, and Boulder Valley schools.

ReadyGEN, a curriculum used in at least seven of Colorado’s 30 largest districts — from Douglas County to Greeley-Evans — passed the first round of evaluation, but wasn’t approved in the second. On appeal, it again failed to win approval.

Cobb indicated in an interview with Chalkbeat earlier this spring that the state might allow more flexibility to districts using curriculums like ReadyGEN, which was previously on the state’s approved list and aligns more closely to state criteria than does Lucy Calkins.