When Sarah Fishering won her Montrose school board seat in 2017, the race was hard-fought but always collegial. She and her opponent jokingly referred to each other as running mates because they spent so much time together at forums and events.

Fishering spent $115 on her campaign. One of her more extravagant expenditures was two-sided printing so she could put a children’s worksheet on a campaign flier.

This year felt much different. A GOP-sponsored candidate forum seemed designed to favor a conservative slate of challengers pledging to uphold traditional moral values, Fishering said. Her opponent from that slate raised more than $1,000, so Fishering overcame her discomfort and asked supporters for money, too.

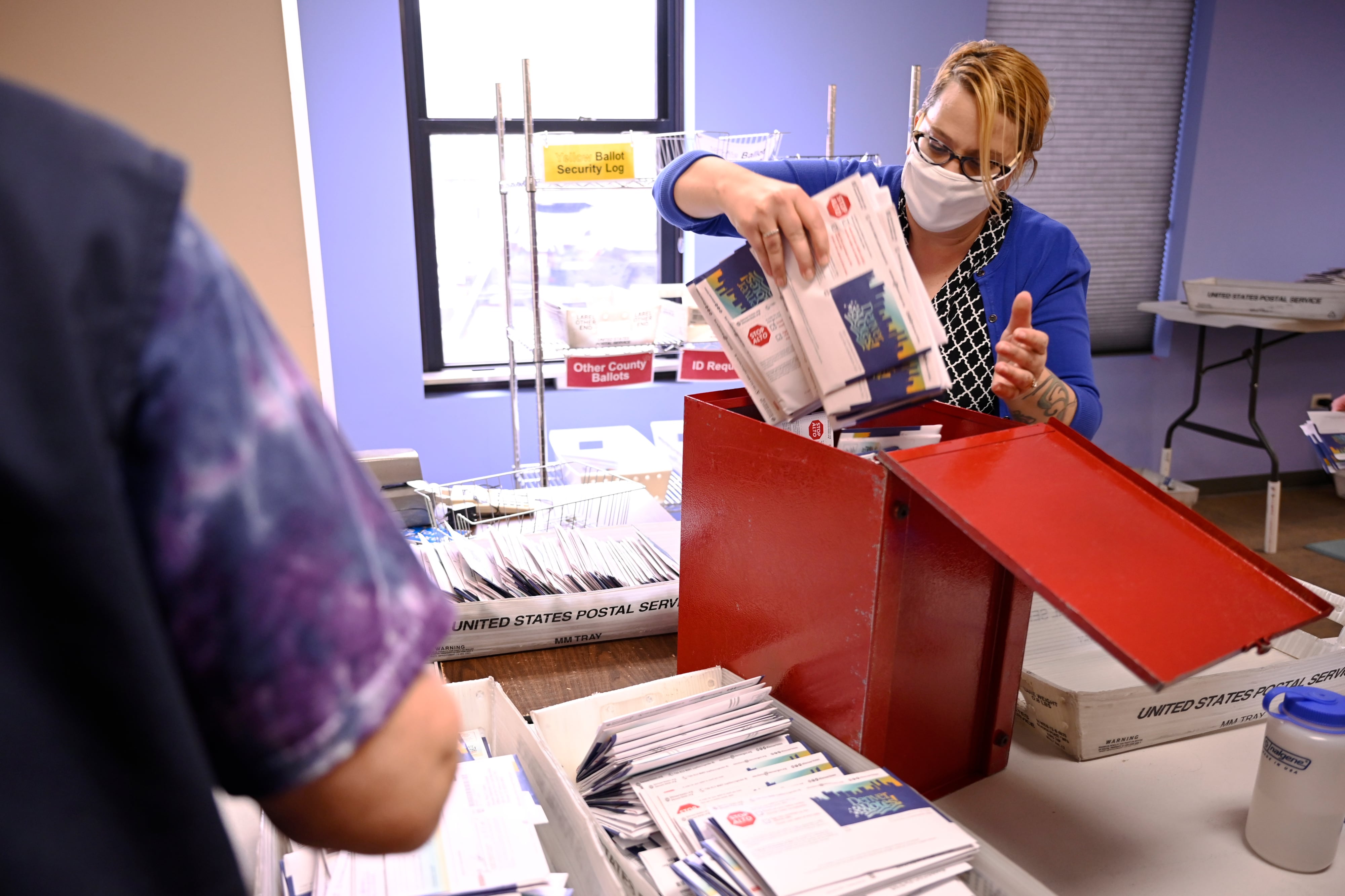

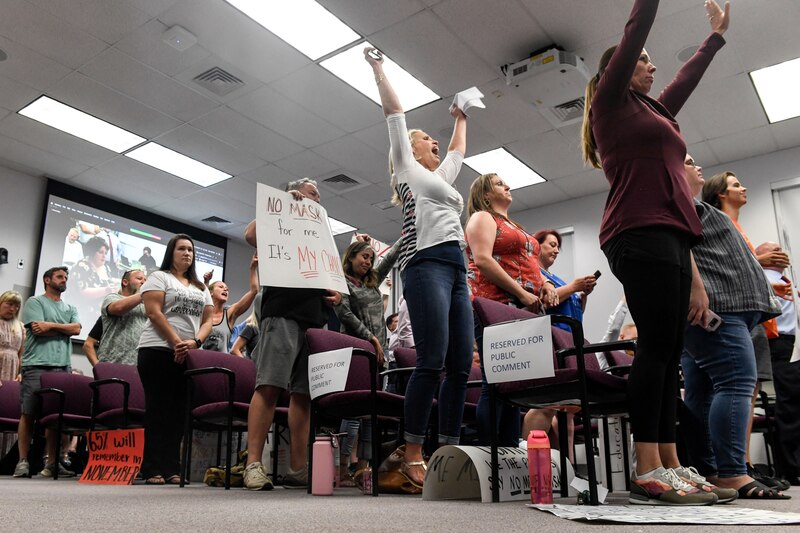

Around the country, school board elections saw a surge of interest and spending, much of it tied to hot-button issues like masks in schools and the teaching of race and American history — and Colorado was no exception. Political observers and education advocates watched to see if a conservative parent backlash would upset the status quo across the state.

Nearly week after Election Day, it is clear that did not happen. While conservative slates dominated in districts that already leaned conservative and Republican, teachers union-backed candidates advocating for progressive values won not only in Democratic strongholds but also in many politically mixed areas that swing back and forth along partisan lines.

More moderate candidates even came out ahead in heavily Republican Montrose County, where Fishering won re-election alongside a like-minded ally. Another incumbent narrowly led in initial results but may be headed to a recount.

“It’s a mixed set of results, and that makes sense given that these are by definition really local political races,” said Anand Sokhey, an associate professor of political science at the University of Colorado Boulder. “In the places where you see more conservative politics emerge anyway, you saw a more conservative trend. In other places, you saw contentious school board meetings and energized races, but the teacher-supported candidates still prevailed.”

School board races are technically nonpartisan, but this year local Republican and Democratic parties endorsed candidates and steered money their way, something not seen in past years to the same degree. In the aftermath, each party declared victory.

How people feel about the risk of COVID and how hard schools should work to prevent transmission largely breaks down along partisan lines. The same is true for ideas about curriculum and how race and history should be taught, often lumped under the umbrella of critical race theory, an approach developed by legal scholars that looks at how laws and institutions perpetuate systemic racism.

Those factors largely explain this year’s school election results, said Ryan Winger, director of data analysis and campaign strategy at Magellan Strategies, a Republican polling firm.

“The nature of these school board races became incredibly partisan, and that’s largely due to how the school boards handled COVID, as well as these pockets where you have conversations about critical race theory or curriculum,” Winger said. “In Republican areas, it’s easier for them to tap into that sentiment because, guess what, there are a lot of Republicans anyway. In places like Jefferson County, it’s a completely different political atmosphere, and it’s not as easy for that conservative slate to tap into that anger.”

Union-backed candidates prevailed in many suburban districts

Conservative slates — candidates who ran on parents having more say in education, against mask and vaccine requirements, and against critical race theory — dominated in parts of the state that already were conservative. Such candidates won in Douglas County, Mesa County, Colorado Springs, and Greeley, and picked up seats in Adams 12 in the Denver suburbs and in the Brighton-based 27J district.

But in more Democratic-leaning and politically mixed areas — Jefferson County, Cherry Creek, Aurora, Poudre, Littleton, and St. Vrain — teachers union-backed candidates who favor stricter COVID safety protocols and a focus on diversity and equity prevailed in hard-fought races.

Statewide, an independent expenditure committee associated with the teachers union spent at least $350,000 to help elect candidates aligned with their views.

In Jefferson County, where conservatives controlled the school board as recently as 2015, union-backed candidates won easy victories over three challengers who wanted better fiscal management and suggested masks harm children’s mental health. The challengers were significantly outspent and may also have struggled under the legacy of the previous conservative board, which made the district the subject of national controversy for efforts to rewrite the history curriculum.

Voters “remember the recalled board,” said Evie Hudak, a longtime education advocate and former Democratic lawmaker, who also noted the county has become significantly more Democratic. “I’m glad to see that Jefferson County voters have a longer memory and remember where we’ve been.”

In Cherry Creek, candidates backed by the teachers union won their races against more conservative challengers. In Littleton, an incumbent secured the most votes while the candidate who made opposing critical race theory his top issue came in last of five candidates.

In the Fort Collins-based Poudre School District, National Education Association President Becky Pringle knocked doors in support of the union-endorsed candidates who went on to win over GOP-endorsed challengers who opposed the district’s mask mandate and wanted more focus on academics rather than equity. And in the Thompson school district, union-endorsed candidates won three open seats, though a fourth went to an anti-mandate candidate.

Republican strongholds elected conservative school boards

The school district in Douglas County southeast of Denver previously had been controlled by a conservative board that implemented a voucher policy that led to years of litigation. In 2017, in an election that drew national interest and significant outside money, a union-supported board took control of the district.

But that board faced significant parent pushback over the past two years over COVID restrictions, hybrid school schedules, and a new equity policy. Students and staff of color have long reported poor treatment in a district where 70% of students identify as white. Most recently, parents railed against the district’s legal fight to enforce its mask order after county commissioners passed a policy allowing anyone to opt out.

On Election Day, a slate of challengers who ran against mask mandates, critical race theory, and aspects of the district’s sexual education curriculum won handily over two incumbents and their allies.

Mike Peterson, a member of the winning Kids First slate, said he first got involved in school board politics after overhearing his daughter’s lessons during remote learning. He thought the lessons divided people into victims and oppressors and taught students from marginalized groups they couldn’t succeed.

Peterson acknowledges the Kids First slate is more conservative than the outgoing board, but he is uncomfortable with describing their win as a backlash. He describes his slate’s focus as restoring the proper place of parent voice and perspective in the educational system, a common framing used by school board challengers this year.

“We just want to get back to academic recovery, academic achievement, get teachers back in their proper place as educators and back in partnership with parents,” he said.

Conservative groups poured money into the Douglas County race and hailed it as a victory, along with another sweep in Mesa County, which saw some of the most contentious school board meetings in the state, with police even escorting members to their cars after one meeting at which some parents called for the superintendent to resign or be arrested.

In Colorado Springs, a political committee with ties to the Republican Party, the Springs Opportunity Fund, spent big to support nine candidates in the three largest districts: Academy 20, District 11, and District 49. All nine candidates were successful, and two incumbents lost their seats. Unlike other conservative slates around the state, this one included incumbents. Ivy Liu, who won re-election in District 49, has been a vocal opponent of critical race theory, and earlier this year, the district became the first in Colorado to explicitly ban its teaching.

Republicans also saw school board victories in Woodland Park, Greeley, and the Huerfano district in southern Colorado.

There was a conservative parent backlash — but it was limited

The pattern in Colorado seems similar to those in school board races in other parts of the country, said Doug Kronaizl, a staff writer with Ballotpedia, an election information site tracking the results from 96 school board races that took place last Tuesday. Ballotpedia isn’t analyzing results by partisan makeup of school districts, but in many districts, candidates running in opposition to mask mandates or critical race theory either won multiple seats — or none.

“It does not appear as if opposing critical race theory [or mask mandates] is a magic wand to win a school board seat anywhere in the country,” he said. “Where they win, they win big. That suggests the district was politically primed for these candidacies.”

In races tracked by Ballotpedia, from 60% to 70% of incumbents won re-election, less than in past years but still a majority. And candidates who supported stricter COVID protocols or a progressive approach to teaching American history were winning about 2 to 1 over candidates who opposed those issues.

A Magellan Strategies poll of Colorado parents found more than half of respondents thought their school and their children’s teachers had done a pretty good job navigating the pandemic so far. This year, Colorado schools have provided more in-person learning, with full-time rather than hybrid schedules and fewer quarantines due to more relaxed state guidelines. That may have eased some of the frustration associated with pandemic education in the lead up to the election.

“I think a lot of the concern came from people who were already going to vote Republican,” Winger said.

Mask politics and CRT didn’t drive every school board race

In Denver Public Schools and in Aurora Public Schools, the races turned more on long-standing disagreements among Democrats and progressives about education reform, the role of charter schools, and the best way to support students, rather than on COVID protocols or the teaching of race.

And some Colorado school districts saw almost no interest in their board races.

The Adams 14 district, which serves a largely working-class Hispanic community in Commerce City, spent more time in remote learning than any other Colorado district, and is under a state order to improve academic performance. The district canceled its election due to lack of candidates, as did other diverse, working-class suburban districts like Westminster, Mapleton, and Sheridan.

Carrie Sampson, an assistant professor at Arizona State University who studies school boards and educational leadership, said communities of color experienced the pandemic differently and that led to different attitudes about masking and other COVID protocols — and in turn different political behavior.

Remote learning “was really hard on those communities, but there was also disproportionate impact of COVID,” she said. “There were more multigenerational families, and people saw family members pass. There was a sense that our communities were at risk.”

The parent backlash “is a phenomenon of white suburban communities,” Winger said.

The school districts where COVID became an election issue were not necessarily those with the strictest policies or where students were most affected by prolonged school closures. Montrose, for example, doesn’t have a mask requirement for students or most staff, but candidates were pressed to say what they would do if the state issued a mandate.

Fishering, the winning Montrose school board candidate, said she ran for re-election in part to protect her district from overheated national rhetoric that was making its way into local education politics.

She credits her victory to a number of factors, including the school district being the largest employer in the county and the conservative slate skipping a key election forum. Fishering said she’s keenly aware that thousands of people voted for her opponent. More than anything, she said she wants parents who felt like they didn’t have a voice to stay involved and see that they do have power to make change in the school system.

“This part of the population that has fallen out of love with our public education system; we have to get them to fall in love again,” she said.