Most Cherry Creek elementary schools rely on reading curriculum that has been rejected by the state and criticized by experts because it relies on debunked methods.

Eighty percent of the district’s 45 elementary and K-8 schools use the program — called Units of Study For Teaching Reading, or more commonly Lucy Calkins. District officials acknowledge the program lacks a strong phonics component and encourages children to guess at words instead of sounding them out.

But the 54,000-student district will use that curriculum for at least one more year. Officials plan to adopt a new core elementary reading program starting in the 2022-23 school year, after first introducing a phonics-focused supplemental curriculum next school year.

Cherry Creek’s story is a familiar one, as districts around Colorado respond to a 2019 state law that put stricter limits on the reading curriculum schools can use in kindergarten through third grade. The law, a revision of Colorado’s landmark 2012 reading law, the READ Act, requires districts to use curriculum backed by science, and state officials have said districts that don’t make a good faith-effort to abandon state-rejected programs could face sanctions.

Buying new curriculum for all of a district’s schools can cost millions of dollars, but advocates hope that, in combination with new state-mandated teacher training requirements, such changes will bolster Colorado’s chronically low reading scores. Only 41% of Colorado third-graders scored proficient on 2019 state literacy tests, the most recent one given.

In Cherry Creek, the proficiency rate was somewhat better at 49%, but boys, Black and Hispanic students, and students from low-income families all scored lower than the districtwide average. In other words, even in the relatively affluent suburban district, lots of children are still falling through the cracks.

For years, Jennifer Abrams’s daughter Eden was one of them.

The 8-year old, who attends the district’s Cottonwood Creek Elementary, has always loved stories and listened for hours when her parents read the Harry Potter series aloud, but she struggled with basic reading skills as far back as preschool.

“She’s really good at guessing,” said Abrams. “When there’s no pictures in the book, she doesn’t want to read it because there’s no picture to give her clues.”

When Eden was in first grade, Abrams requested a special education evaluation, but the district determined her daughter didn’t qualify for services. Instead, the district found that Eden had anxiety and executive function issues and provided some accommodations for those challenges.

Last fall, in second grade, Eden continued to struggle. She knew other children were starting to read chapter books on their own, but she wasn’t. She felt dumb. Abrams finally took her daughter to a private evaluator and Eden was diagnosed with dyslexia.

Abrams said she feels problems with reading instruction are systemic, not the fault of teachers. But she wonders if Eden would have avoided skill gaps and low self-esteem if her school had used a different curriculum that directly teaches students about letter-sound relationships in a methodical way.

“She will always be dyslexic but would she be behind if we had started with a phonics-based program?” Abrams asked.

Why state-approved matters

While most Cherry Creek schools use the Lucy Calkins curriculum, about 20% use other programs. None use state-approved core reading programs — the comprehensive curriculum intended for all children in a classroom.

Colorado schools don’t technically have to choose a core K-3 reading curriculum endorsed by the state, but choosing from the state’s approved list can avoid a lot of headaches.

That’s because the dozen core curriculums on the recently revised list — 10 English-language and two Spanish-language programs — have all been vetted by state reviewers who determined they are evidence- or scientifically based. That phrase, evidence or scientifically based, is the operative term when it comes to acceptable reading curriculum in Colorado.

State-approved programs meet that criteria, while programs the state has reviewed and rejected — such as Lucy Calkins — do not. What’s still unclear is how the state will handle schools that use programs it hasn’t reviewed at all.

In Cherry Creek, that likely won’t be a major issue since leaders are already planning to switch. They’ll start by adding a phonics-focused supplemental curriculum — Fundations — next year. Next, they’ll adopt a new core curriculum off the state’s approved list, with use in kindergarten and first grade starting in 2022-23 and in second and third grade starting in 2023-24.

The timeline feels slow to some parents — given this year’s kindergarteners won’t receive instruction using a state-approved core curriculum until they’re in third grade.

“What are we waiting for? These kids need it now,” said Selena Roth, who has a seventh grader with dyslexia and is part of a Colorado dyslexia advocacy group. “I know it’s a big ship, but they can still turn around.”

Veteran third-grade teacher Diana Martin-Gruenler, who said she spoke on her own behalf not as a representative of the district, supports plans to adopt a new curriculum across all schools. However, she worries about the heavy training burden on teachers — both learning the new curriculum and taking the new state-mandated training on reading instruction

This year, she said, she’s just trying to keep her head above water.

Her school, Peakview Elementary, uses a curriculum called Reading Street in some grades, and what she called a potpourri of materials, including from the Teachers Pay Teachers website, in others.

When Martin-Gruenler began teaching 37 years ago, phonics was in vogue, but when she later went back to school for her master’s degree in reading, there was no mention of it, she said.

“Overall, I do not have a problem with an emphasis on phonics and bringing that back in because I think it’s an important part,” she said.

Literature at their fingertips

Like many districts, Cherry Creek historically let schools choose their reading curriculum. Many opted for Lucy Calkins, which despite its critics has been popular in Colorado and the nation for years.

Diana Roybal, Cherry Creek’s executive director of elementary education, oversaw the adoption of the Lucy Calkins curriculum at two district schools where she served as principal, including one that served many low-income students. About 30% of the district’s students come from low-income families.

Before the adoption of Lucy Calkins, there were no classroom libraries and children learned to read using an anthology, she said.

“There wasn’t lots of literature at kids’ fingertips where they could just immerse themselves in literature and all kinds of genres of literature,” Roybal said. “What I appreciated about Units of Study is it really helped kids develop an academic identity as readers and writers.”

Last year, in a review of the program, seven reading researchers lauded the program’s emphasis on “loving to read,” but also found serious flaws. They said the program dedicates too little time to phonics, includes almost no support for English learners, and encourages students to guess at words, a method that runs counter to a large body of research.

Last fall, Calkins herself, co-author of the curriculum, backtracked on her long-standing support for guessing.

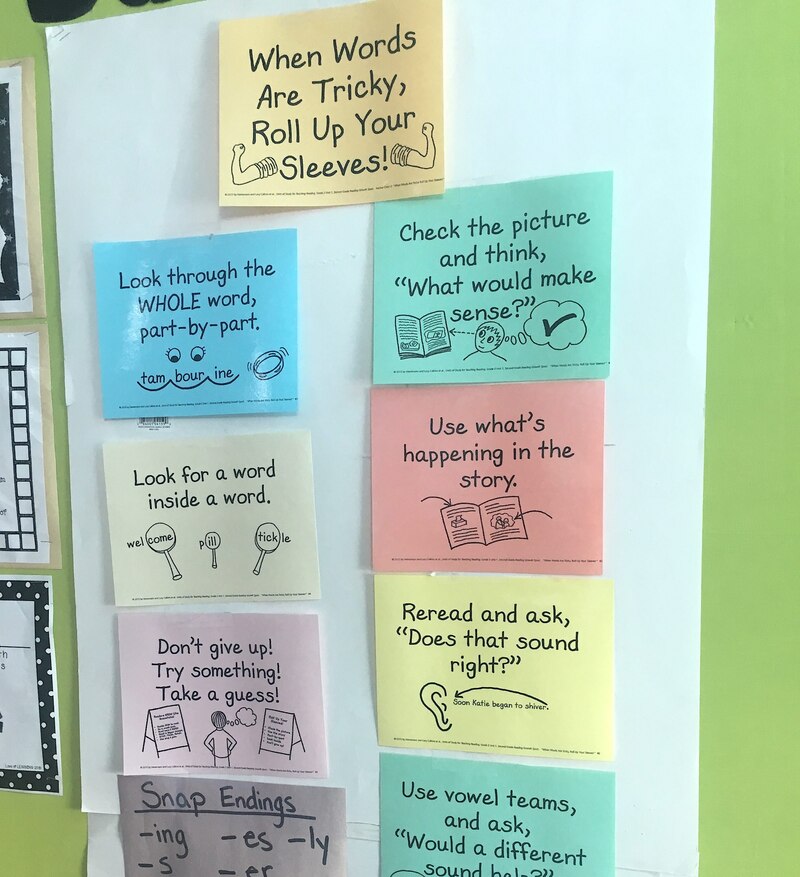

A document circulated last fall by Columbia University’s Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, which Calkins founded, called guessing based on pictures “an inefficient way for the reader to proceed.” It said teachers should instead tell children to “respond to tricky words by first reading through the word, sound-by-sound, (or part by part) and only then, after producing a possible pronunciation, check that what she’s produced makes sense given the context.”

Despite that shift, and several others detailed in the document, it’s unclear when Calkins will release revised curriculum materials that align with her evolving beliefs. In a Facebook Post last October, she said her team is writing a series of “decodable books” — books that highlight phonics patterns students are learning — and adding a phonemic awareness curriculum.

Roybal acknowledged the shortcomings in Calkins’ program, particularly when it comes to phonics and phonemic awareness — the ability to identify and manipulate the sounds in spoken language.

She said if she were still a principal, “I would definitely have invested in that component because there is still a definite need for some direct instruction in concrete foundational skills around phonemic awareness and phonics that probably wasn’t as direct in Units of Study.”

Who else is falling through the cracks?

Abrams recently read a book about Mars with Eden. The second-grader stopped when she came to words like planet, canyon, and crater.

“She could not get the multisyllable words,” Abrams said. “She stopped and paused and kind of looked at me.”

Abrams, who is also part of the dyslexia advocacy group, knows it will take awhile for Eden to catch up to her peers, but her daughter is making progress with the help of private tutoring sessions. More recently, Eden joined a special pull-out reading group at school.

Still, Abrams feels frustrated that for so long she didn’t know why her bright daughter couldn’t keep up or what exactly was missing.

“People started to make me feel like I was the crazy one,” she said.

While Abrams considers the district’s plan to adopt new reading curriculum a good step, she knows there are other flailing readers out there who aren’t getting the help Eden does.

“I’m a pushy parent with resources, that’s the reality,” she said. “It still took me three years to get there.”

Search for a Cherry Creek school below to find out what core reading curriculum it uses in kindergarten through third grade and whether that program has been approved by the state. A core program is a comprehensive instructional program designed to teach all children in a classroom.