All Denver school buildings will get air quality sensors this summer as part of a broader pandemic-fueled effort to improve the air students breathe.

Denver Public Schools is spending $1.5 million on about 800 sensors, which will be placed in 10% of the district’s classrooms, a spokesperson said. The $1.5 million is a small fraction of the $205 million in federal COVID stimulus money, known as ESSER funds, that the 90,000-student district received. The district must spend the money by 2024.

“We know now, more than ever, that good indoor air quality contributes to a favorable environment for students and staff, and is part of assisting a school with its core mission of educating children,” district spokesperson Scott Pribble said in a statement.

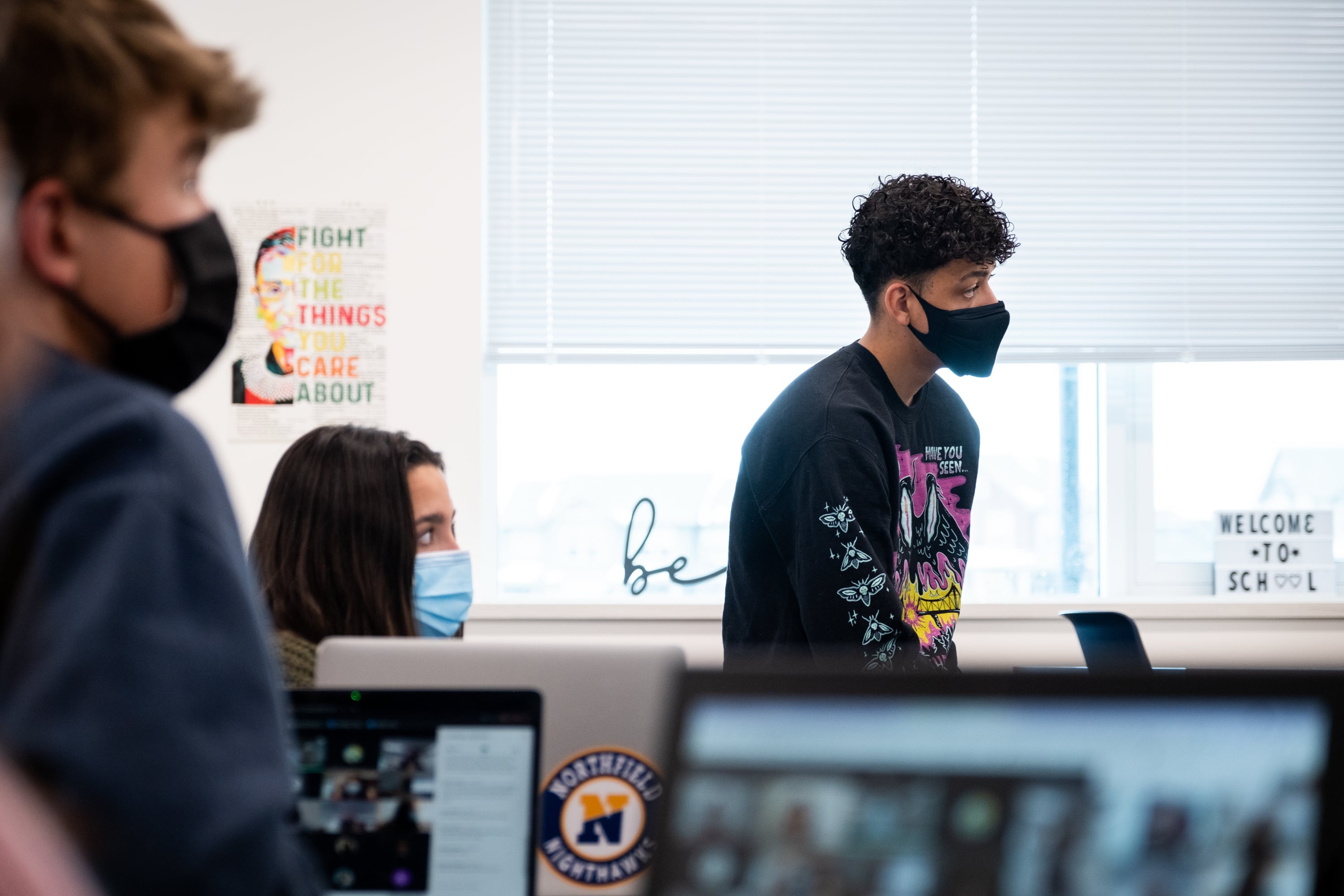

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused educators and families to question the air quality inside schools, an aspect of public education some researchers said got too little attention for too long as students suffered with allergies, asthma, and airborne viruses that can disrupt learning.

Districts around Colorado and the nation are scrambling to use federal COVID funding to address the issue, sometimes buying air cleaning systems that scientists warn are unproven.

But two experts at the University of Colorado Boulder said the sensors Denver Public Schools has purchased are a smart way to help prioritize how and where to improve air quality.

“You can’t monitor what you don’t measure,” said civil engineering Professor Mark Hernandez, who ran an air filter pilot project at 17 Denver schools last year. “It’s meant to help them prioritize: ‘Let’s find the worst-performing buildings or classrooms first, and let’s start with those.’”

Made by a company called Senseware, the sensors continuously monitor air temperature, humidity, carbon dioxide, particulate matter, and volatile organic compounds in the air to gauge whether a school’s ventilation strategy is working, co-founder and CEO Serene Almomen said.

The information they collect is displayed on an online dashboard. The system can send real-time email or text alerts if the sensors detect a problem, Almomen said.

If a classroom’s carbon dioxide level is high, it might indicate there are too many students in too small of a space, which could be addressed by increased social distancing, she said. If particulate matter readings go up, it could mean it’s time to change the air filters or add a portable unit to the classroom, a strategy that Hernandez’s pilot program found worked.

Many cleaning products emit volatile organic compounds, and Almomen said the sensors can help ensure schools don’t unintentionally create new problems while solving other ones.

“The whole idea is keeping things at the right healthy level around the clock,” she said.

Denver Public Schools said Senseware will send notifications to the district’s environmental services department. If the department suspects there’s a maintenance issue with the ventilation system at a school, they can put in a request to fix it. The data from the sensors will also show trends that the district can use to plan future work, Pribble said.

Senseware has installed sensors in schools across the country, including in Washington, D.C., Chicago, and Atlanta, a company spokesperson said. In addition to the sensors, Denver Public Schools is using ESSER money to add digital controls to schools’ heating and ventilation systems to centrally regulate things like temperature and outside air exchange, Pribble said.

The district also is repairing and replacing HVAC components like exhaust fans and boilers, and is building more outdoor classrooms. Two years ago, it spent nearly $5 million to repair HVAC systems, clean the equipment, and upgrade school air filters to either MERV 11 or 13, depending on what the system could handle.

Nicholas Clements, a mechanical engineering postdoctoral research associate at CU Boulder, said those types of upgrades are key to effective sensors.

“If you spend money on sensors but manage your buildings as before except for a couple service tickets, I don’t always see the value in that,” Clements said. “Sensors are not as successful as a one-off project if you’re not also upgrading other systems.”

Denver already monitors outdoor air pollution at some schools, but both Clements and Hernandez said the increased attention indoors is a step forward.

“There is a lot more attention on indoor air quality as a result of the pandemic,” Clements said. “Of the buildings that need the most attention … schools are a big one.”

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.