Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free monthly newsletter The Starting Line to keep up with news about early childhood education.

“Would you rather eat only chocolate or only marshmallows?” teacher Jordan Parsons asked the gaggle of preschoolers sitting on the rug in front of her.

Most of the 13 kids bounded to the left side of the rug, several gleefully jumping and shrieking at the thought of a marshmallow-only diet. A few chocolate-lovers drifted to the other side of the rug.

When Parsons asked which group was bigger, a member of Team Marshmallow confirmed the obvious: “This one,” he said brightly.

It was the first day of preschool at Denver’s Auraria Early Learning Center and part of the rolling launch of universal preschool in Colorado. The new $322 million program offers 10 to 30 hours a week of tuition-free preschool to 4-year-olds statewide and 10 hours to some 3-year-olds.

Up to 40,000 4-year-olds are expected to participate in the program this school year, double the enrollment of Colorado’s previous state-funded preschool program.

Many parents and early childhood advocates are excited about the state’s effort to help more families with preschool costs and prepare kids for kindergarten. At the same time, some aspects of universal preschool rollout have been rushed, confusing, and punctuated by eleventh hour changes.

Thousands of families who had expected the state to cover full-day preschool based on meeting certain criteria found out in late July the program would only pay for half-day classes. Most recently, school district officials sued over the program, claiming the state is harming students with disabilities and breaking funding promises to families and schools. Religious preschools also have sued, alleging that anti-discrimination requirements violate their religious beliefs.

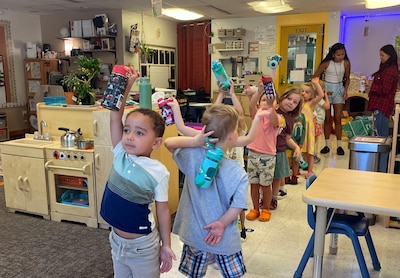

But on Monday morning, the kids in Parsons’ classroom were unconcerned with legal questions and logistics. They were too busy with playground time, the “Would you rather?” game, and a story about a dinosaur named Penolope who ate her classmates.

The problems they did have were child-sized: A forgotten water bottle, outdoor playtime cut short by the melting heat, and a few pangs of homesickness that called for a break in the “cozy cove” — a large wooden hideaway stocked with a basket of toys.

A little girl in a pink and green sundress said her favorite part of preschool is “using scissors” — purple glittery scissors, to be exact.

A boy who proudly announced he’d just turned 4 in July, said he enjoys drawing — especially rainbows, like the one on his first-day-of-school shirt.

“I picked it out from Target,” he said of the green top.

For her part, Auraria Early Learning Center Director Emily Nelson said she’s pleased with how universal preschool is shaping up. There have been challenges, but that’s true with any new system, she said.

“I feel good with where we’re at,” she said. “I feel like parents have the information they need.”

She’s heard some parents express relief that the state is helping defray tuition costs. Under universal preschool, the state covers the cost of 15 hours a week at the center, dropping monthly full-day tuition from $1,531 to $921. Some parents get additional assistance through campus scholarships or a taxpayer-funded tuition credit program called the Denver Preschool Program.

Like many providers across Colorado, Nelson had empty universal preschool seats on the first day of school — eight between her two 4-year-old classrooms. Statewide, about 56,000 4-year-old seats are available, well above the number that will be needed even if more families sign up in the coming months.

Nelson said having a few open seats is typical at this time of year, especially being on a college campus where classes are also just beginning. The center serves the children of students, faculty, and community members.

When the semester starts, parents think, ‘Oh child care, I need to figure that piece out,’” she said.

On Monday, the children at Auraria Early Learning Center had their own challenges to figure out. A ponytailed girl announced during storytime that she felt sad. Then she went into the cozy cove and emerged rejuvenated — ready to get back to her first day.

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org