Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

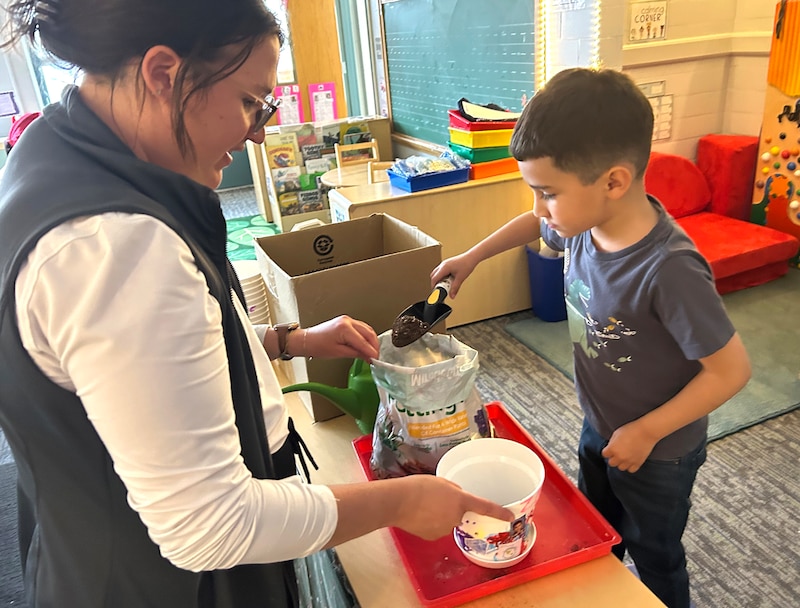

Stavros, a 4-year-old at Denver’s Palmer Elementary School, stood on a low blue chair scooping soil into a white pot he’d decorated with his school picture and stickers of a donut, a camera, and the word “lucky.” Next, he shook in a packet of seeds for wildflowers native to Colorado and swirled them around with his index finger.

“What else do we need?” asked preschool teacher Raegan Haines.

“Water!” squealed the little boy.

“Nailed it,” she said.

The gardening activity on a rainy May day is one way Haines tries to give her students experience with nature and build early habits in environmental stewardship. These activities — hands-on and age appropriate — are the kinds of things experts say help stave off worry about the fate of the natural world. In short, eco-anxiety.

Recognized by the American Psychological Association, the term is most simply defined as the chronic fear of environmental doom. Across Colorado, many early childhood educators are creating teachable moments meant to combat the sense of sadness and hopelessness that can come with it.

Though most small children don’t know what climate change is, they’re not immune to its frightening impacts, including floods, wildfires, and extreme heat — all of which can affect children from low-income families more acutely than their higher income peers. Alarming information about climate disaster can also reach kids indirectly, through snippets of adult conversations and imagery from 24/7 news.

“I can see why kids are feeling like this, because they have so much access to media all the time,” said Haines. “When I was growing up, I didn’t know about the wildfires in California unless they were really, really bad.”

Haines was among about two dozen child care and preschool teachers who recently filled a small room for an early childhood conference session on mitigating eco-anxiety. Some said they were interested in the session because they feel anxious about climate change themselves or because they’d seen anxiety in general spike among their young students.

One woman said she’d decided to attend the session after a startling conversation with her 12-year-daughter.

“Her teacher had told her by the time she’s 25 … she will not be able to show her kids certain parts of the ocean and there’s a lot of animals that are not going to be there,” she said.

Liz Beaven, one of the presenters and president of the Alliance for Public Waldorf Education, had a name for that: “Scaring the kids to death.”

Even well-intentioned lessons can backfire, she said, prompting kids to shut down or become wildly anxious.

“We need to balance the information with a sense of possibility,” she said.

Creating an outdoor oasis in a shopping plaza

Experts say early childhood teachers can give kids experiences that bolster their appreciation for nature even if they don’t have ready access to parks or wild places. It’s as simple as letting kids dig in the dirt, plant flowers or veggies, and use leaves and pinecones for crafts — the kinds of things many teachers already do.

Step by Step Child Development Center, a Northglenn child care center that serves many low-income families, is housed in a former furniture warehouse in the corner of a strip mall. Behind it are apartments and next to it a new senior living complex is going up.

Over the last several years, grants from the National Wildlife Federation’s Early Childhood Health Outdoors program have helped the center revamp three playgrounds and an outdoor breezeway so they’re more conducive to nature exploration. None of them are fancy, but they all aim to make the outdoors interesting and accessible.

The breezeway has raised beds for gardening, plus one called “The Worm Patch” where kids can dig in soil populated with hundreds of earthworms that center Director Michelle Dalbotten orders online. The infant playground is ringed with low garden beds that contain edible plants (but no fertilizer since curious babies might try to eat it).

The toddler playground includes a wooden deck where children sometimes eat lunch or take naps. On a recent spring day, a 2-year-old girl offered a visitor a handful of dirt, saying, “Lick it.”

A teacher quickly interpreted the gesture, asking, “Are you trying to give her the cupcakes you were making?”

On the preschool playground, the large plastic play structure that was once its centerpiece is long gone. Now, there are raised garden beds, a “mud kitchen,” tunnels propped on boulders, bins full of logs, a teepee for alone time, a curving paved path, and an open air playhouse. Next, Dalbotten wants to install a string of tree stumps.

In early May, the star of the show was a mud puddle. Preschoolers jumped into the brownish water, stomped through it, dropped rocks in it, and dangled a blue action figure into it so he could “swim.”

Neither teachers nor students worried about the water splashing onto pants, coats, and boots. The center warns parents that outside time means getting dirty and stows carts full of dry footwear by the front door.

Dalbotten said the yearslong outdoor transformation has made students and teachers more enthusiastic about spending time outside.

Gazing at the playground, she said, “This is more fun than throwing the same truck off the same slide 200 times.”

Changing the world in kid-sized ways

As kids have more experiences with nature, they are primed to to improve their corner of the world,

“Collective action,” said Cathrine Aasen Floyd, an early childhood consultant who presented with Beaven at the eco-anxiety session. “We know there’s negative things going on, but there’s a lot that we can do to make these positive changes.”

Jenni Bauderer, a plant-lover who teaches 2-year-olds at Step by Step, tries to include small lessons about plant life and gardening at least twice a week.

“I just think it teaches them more respect for life in general, because most people don’t think about telling a 2-year old about plants and that they’re alive,” she said.

Bauderer begins with planting practice in the classroom sensory tables. The toddlers push seeds into dirt, water them, and talk about how they need sun to grow. Sometimes, she stages fake blooms in the garden during nap time so the kids find flowers when they wake up.

Bauderer sees the impact of her lessons when new children join the classroom.

“We have one giant succulent in the middle and they just go in and start ripping it apart, and other friends will be like, ‘Noooo!’”

At Palmer Elementary, which in the fall will switch from an elementary school to an early childhood center, Haines also offers child-friendly lessons with real-world applications.

This spring, 3- and 4-year-olds learned about the dangers of ocean garbage and the benefits of recycling through a picture book called “Save the Ocean.” It’s about a sea turtle who accidentally eats a plastic bag and a mermaid who saves him.

After reading the book, the preschoolers worked with fifth graders to transform old water bottles, yogurt containers, and toilet paper rolls into an oceanscape of sea creatures for a hallway display.

During circle time, Haines sometimes brings out miniatures of everyday products — salad dressing, crackers, and baby wipes — and asks each student to decide whether the packages should go into a tiny blue recycling bin or a green garbage bin.

“We talked about soft plastic versus hard plastic, and tin and paper and cardboard,” she said. “If somebody needs help, we’ll all help figure it out.”

One little girl didn’t need help finding a fix for the ocean garbage problem. She came to class one day with a no-nonsense proposal.

“Miss Raegan, we get a big crane and we go into the ocean and we scoop it all out, and then the animals will be OK.”

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org