Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

The kindergartner in the light blue Bart Simpson T-shirt was quick to say “no” when Quianna Becenti asked him if “horse” starts with the “h” sound.

“Nooooo?” Becenti asked in an affectionate sing-song voice. “Listen to the beginning … horse.”

The 5-year-old gazed at the smiling cartoon horse on his worksheet and reconsidered. He repeated the word in a breathy voice, nodding as he heard the “h” sound.

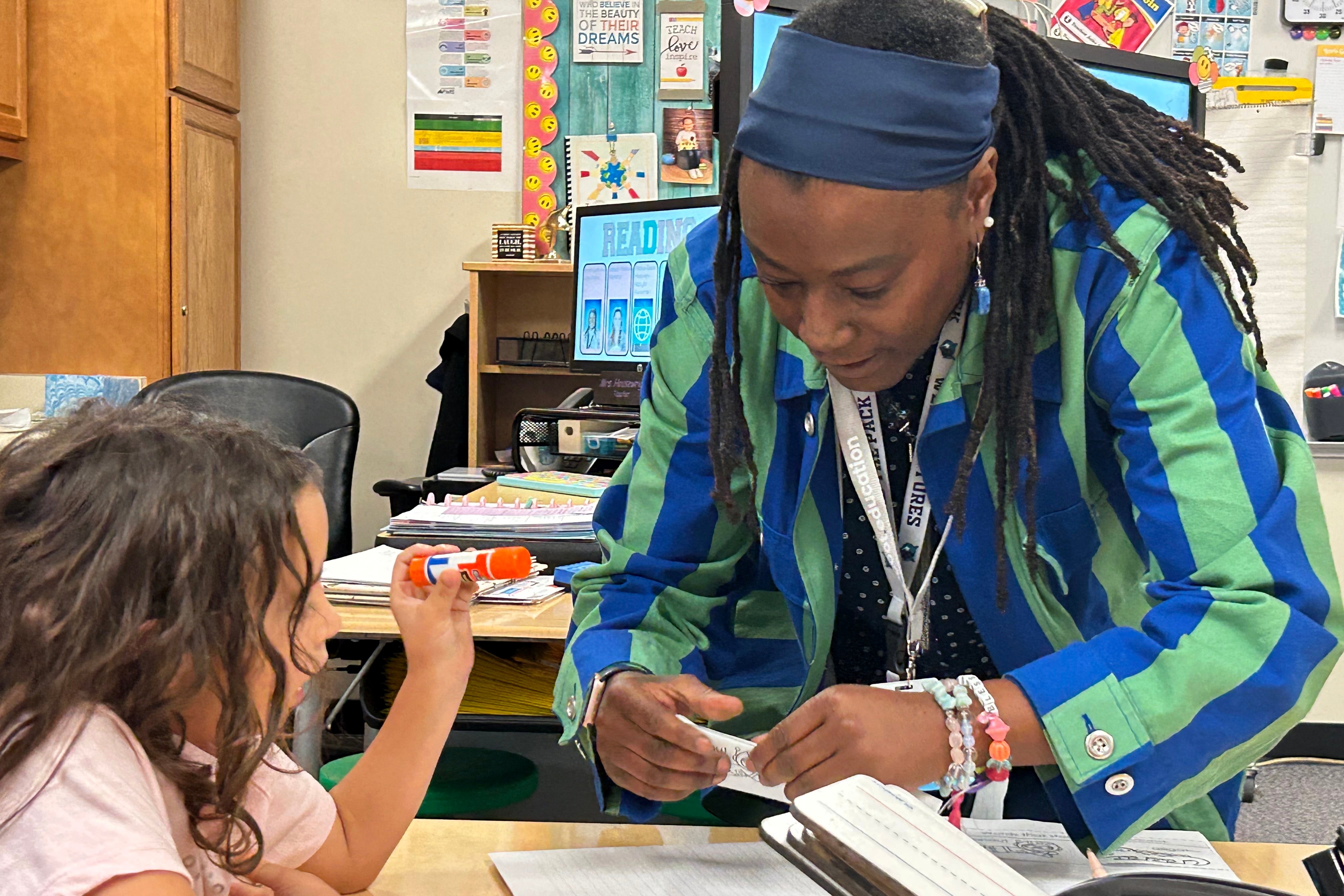

The moment was a step on the little boy’s road to reading at Mesa Elementary School in the Westminster school district north of Denver. Becenti, a paraprofessional, is part of a new $1 million district effort to boost early reading skills by adding paraprofessionals to all kindergarten classrooms.

At a time when many Colorado school districts are tightening their belts because of state and federal budget cuts, Westminster’s initiative represents a bet that offering kids more personalized help from trained adults will improve reading outcomes.

Like many districts, Westminster Public Schools, where about 40% of students are English language learners and most students come from low-income families, has struggled to get students back on track after the pandemic. Over the summer, district officials received discouraging news: After an eight-year reprieve, the 7,700-student district was back on the state watchlist for schools and districts with low ratings.

Ratings are largely based on state test results. Scores from last spring show that only about 23% of Westminster’s students are reading and writing at grade level, compared with 45% statewide.

Across Westminster’s 24 kindergarten classrooms, paras like Becenti give students more small group instruction and one-on-one attention than they would get with only a classroom teacher.

The new literacy effort won’t generate quick results on state tests, district leaders say. That’s partly because today’s kindergartners won’t be in third grade — the year state testing starts — for three more years.

It’s about playing the long game, said Mat Aubuchon, the district’s executive director of learning services. That means working harder to build foundational skills among the youngest students rather than simply offering remedial help as they get older.

“If you don’t develop a reader by the time they’re walking out of first grade, they have a hard time catching up,” he said. “This is intended to be an early investment to say, ‘How do we offset that?’”

Aubuchon said he expects the district will fund the effort for at least two years and possibly more.

The district used a multinational staffing company called Scoot Education to hire two dozen new kindergarten paras over the summer. Most get paid $22 an hour, with bilingual paras getting a little more. Compared with most other paras Scoot supplies to local schools, the early literacy paras in Westminster get more structure, support, and training, said Colleen O’Malley, an educational consultant at the company.

Becenti, who graduated from nearby Thornton High School and has completed some college, used to consider herself a “kid-hater.” Not anymore. After a stint at a swimming school, then a child care center, she found she loved working with children. At Mesa Elementary, she likes watching students make big learning gains.

“Even just from looking back at our first week and seeing where they were at versus now, it’s like, wow. It’s crazy,” said Becenti, who now aspires to become a teacher.

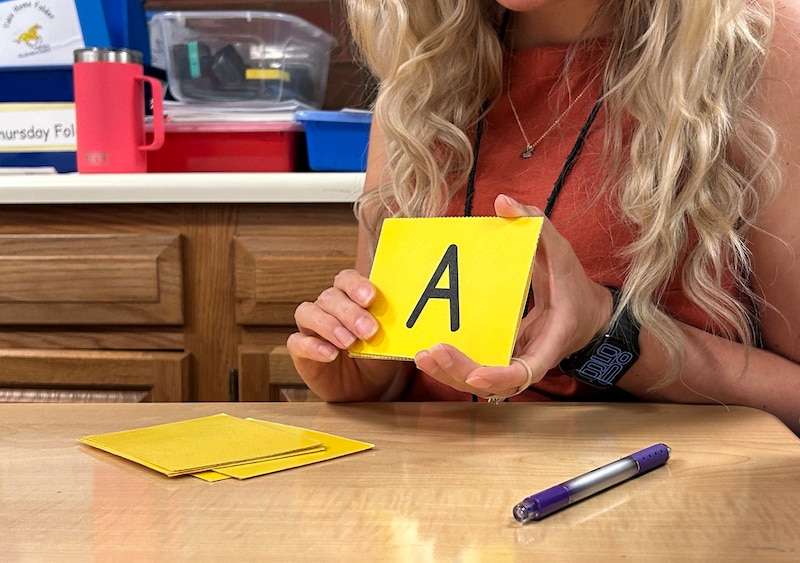

On a recent September morning, Becenti, whom students call Miss Kiki, worked with a group of four students on the letter H. She articulated the airy H sound over and over, adjusted their grip as they used crayons to draw the letter, and quizzed them on the beginning sound of heart, hat, house, and — just to make sure they got it — nest and monkey.

Nearby, teacher Kristina Cleveland worked with another small group on the letter L, practicing with words like “legs,” “lips,” and “lid.” A third staff member, who only spends a short time in the room each day, worked on letter flashcards with three children. Another handful of students practiced independently on computers.

With Becenti in the room, “It’s just nice because there’s more reinforcement,” Cleveland said. “My concern’s always been sending a kid away, especially a 5-year-old … and them practicing something I’ve taught them incorrectly.”

Research shows that small group instruction in phonemic awareness, a key early reading skill that enables children to identify and manipulate the individual sounds in spoken words, can be more effective than whole class instruction.

During a morning break, Cleveland pulled up a chart tracking her students’ progress on the eight letters and sounds they’d learned over the previous few weeks. It had a lot more green than white — a good sign.

“I just did DIBELS testing,” Cleveland said, referring to a common elementary reading assessment. “We’re way ahead for first sound fluency at this part of the year than I think we’ve ever been, because they’re getting three doses” of practice.

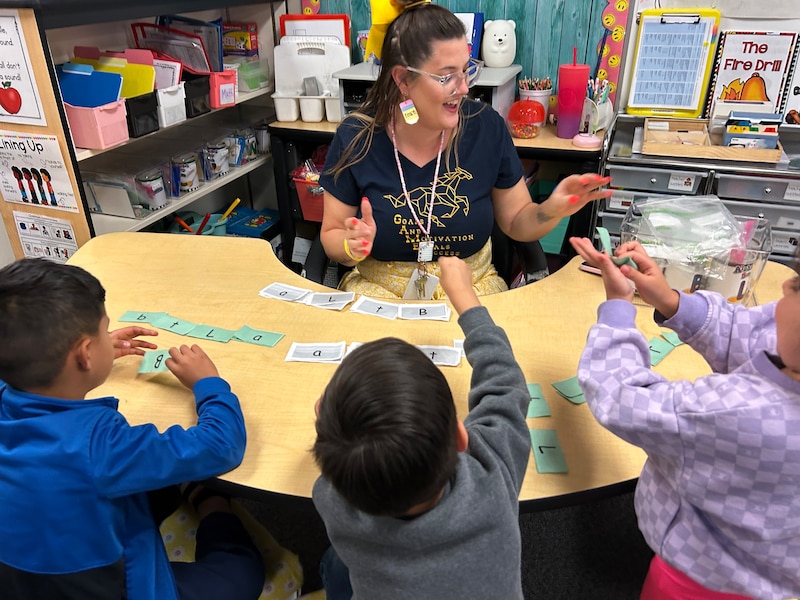

Brandi Housewright, the other kindergarten teacher at Mesa Elementary, said her paraprofessional, Zatina Gardner, is also helping the kids make progress. By the end of the year, she hopes their students will have better blending skills than previous classes did. That is, the ability to look at a series of letters, such as C, A, and T, and smoothly combine the sounds to say “cat.”

“The jump from kinder to first grade, people don’t realize it’s a big jump,” Housewright said. “And with the second person, we’re going to be able to make that jump without having gaps.”

Gardner, who previously worked with teens as a mentor and tutor and is planning to earn her teaching license, was constantly in motion on a recent morning. She was standing before two boys and two girls in the pink reading group, the lowest in the class. She led them in a fast-paced letter-naming game. A boy in a Super Mario hoodie was particularly quick on the draw, soon amassing a stack of white cards with letters he’d called out first. Across the table, the other boy had no cards, often naming the letter a beat later than his groupmates or not answering at all.

Such struggles aren’t lost on Gardner or Housewright. The two meet regularly to talk about student needs, even delving into how to seat students so they are benefitting most from their nearest classmate.

Housewright said the early literacy effort is valuable because it puts an extra set of eyes in the classroom.

“If it gets taken away … I will cry and throw a fit like a kindergartner,” she said laughing.

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.