How much do schools need to make the coming school year work — and how much federal help will they get?

Those are the fundamental questions facing Congress as it begins negotiations on an additional coronavirus relief package. The answers will help shape when schools physically reopen, whether many teachers and other school staff lose their jobs, and how effectively schools can respond to learning loss that likely resulted from a spring of remote instruction.

There are a lot of big numbers being thrown around, and now that Senate Republicans have introduced their proposal, competing plans. Here’s a cheat sheet.

What new costs schools face this year: Over $100 billion, according to one estimate

What do schools need this year that they didn’t last year?

Some estimates of this combine two separate issues facing schools: new expenses resulting from the virus and shrinking budgets thanks to the virus-related economic recession. For clarity, we’ll focus on them separately.

The American Federation of Teachers compiled what appears to be the most comprehensive estimate of the new costs schools will face this year. It includes new staff to allow for social distancing, personal protective equipment, technology for continued remote learning in some cases, and extra learning time for students who are behind. All in, this would cost $116.5 billion, or over $2,000 per public school student.

Two caveats: One, that figure is based on a subjective accounting of what schools need by the AFT, which is making the case for a large funding package. And some of their costs, like extra learning time, aren’t necessary to reopen safely. Two, the estimate was released in June, when there was more optimism that most schools would physically reopen in the fall. With many schools remaining physically closed at the start of the year, they might save a little more money.

What state governments stand to lose over the next few years: Over $500 billion

Schools face another problem: a precipitous drop in tax revenue that is squeezing education budgets.

When the economy is weak, dollars collected by the state government — like state income taxes and sales taxes — decline, because people are earning and spending less. That money is a major source of education funding, particularly for high-poverty school districts.

One analysis estimates that over two years, state budgets will be short $603 billion. Another estimate pegged the total state shortfall at $555 billion over three years. Since about a third of state dollars go to K-12 education, this creates a big problem for schools.

A few caveats: these are informed projections, but the actual revenue drop will depend on how the economy recovers, and some states are likely to be hit much harder than others. These estimates also don’t include potential declines in local revenue, another key source of school funding.

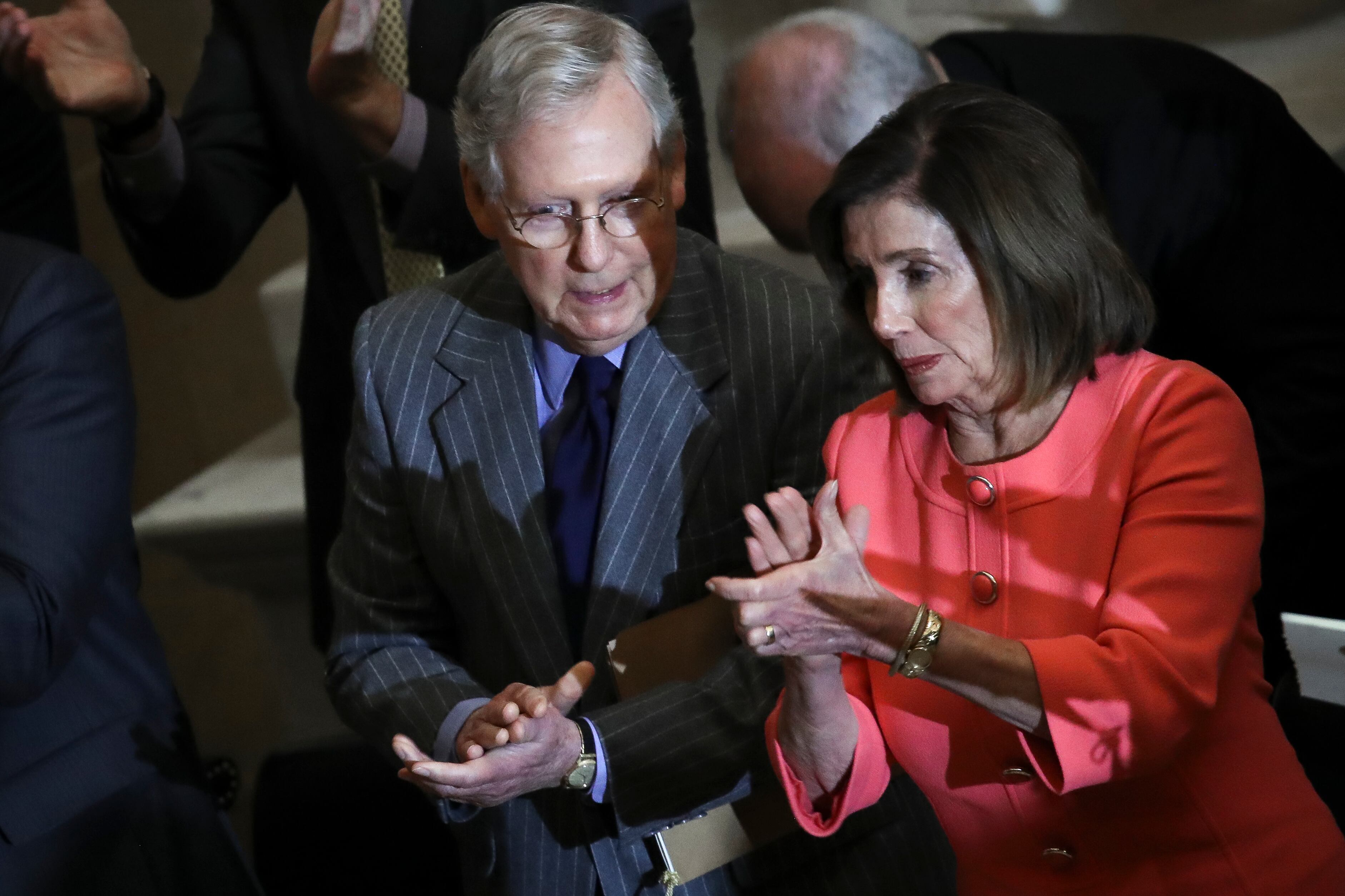

What House Democrats passed: $500 billion for states, $58 billion for public schools

So what are Congressional leaders considering to address schools’ budget stress?

It’s very clear what Democrats in the U.S. House want, since they passed a bill known as the HEROES Act. It amounts to $3 trillion, including $58 billion for public schools and $500 billion to help fill state budgets.

The state money isn’t earmarked for schools, but they would likely get some of it. (The bill also included a large pot of money for local governments, but most school districts wouldn’t have access to it.)

These are really big figures, considering the federal government usually spends $57 billion on K-12 schools annually, or about $1,000 per student. In other words, the HEROES Act would dramatically increase the federal government’s role in funding K-12 education.

At the same time, these figures are comparable to the estimates above of the extra costs and declining revenue schools are facing. Many economists say this is exactly the moment for the federal government to step in, arguing that such help will goose the economy by saving public school jobs.

Money is also likely to translate into better outcomes for students. During the last recession, states that made bigger funding cuts saw greater declines in student learning. Moreover, after that recession, school budgets took several years to fully recover.

What Senate Republicans are proposing: $0 for states, $70 billion for public and private schools

Senate Republicans are proposing sending $70 billion to K-12 schools, two-thirds of which is earmarked for schools that physically reopen. That stipulation is opposed by Democrats and education groups.

The bill also includes money for private schools, which would be allocated based on their share of students in each state. Nationally, 10% of K-12 students are in private schools, meaning roughly $7 billion would go to those schools.

The Republicans’ all-in number for schools is comparable to House Democrats’ figure in the HEROES Act. But there’s a big catch: the Senate bill does not include any funds for state governments. That means that public schools would almost certainly get less under the Republicans’ proposal. (House Democrats have also emphasized that they recently passed a bill that includes additional money to improve school facilities.)

Some conservatives have argued against further growing the federal deficit and suggested instead that schools should make staffing cuts.

What Congress already passed: Over $13 billion for schools, about $60 billion for states

Congress already passed a large virus coronavirus relief package known as the CARES Act. It included $13 billion for K-12 schools, though much of that hadn’t reached schools as of the end of May. Additionally, nearly $3 billion went to state governors to distribute to K-12 schools and higher education institutions.

The CARES Act also allocated $150 billion to state and local governments for coronavirus expenses. About $60 billion of this is earmarked for states. Some of those dollars have been passed along to schools, though it’s not clear how much. (The new Republican bill includes a provision to allow CARES Act money to be used in new ways, including to fill budget holes.)

Regardless, the estimates above suggest that the CARES money won’t be enough to fully respond to the pandemic or fill education budget gaps. Moreover, some states simply cut school budgets by amounts comparable to what schools received from the CARES Act, further limiting the impact of those dollars.

What schools have saved from building closures: It’s not clear

There is one silver lining for school budgets: building closures and remote learning were likely cost savers.

Yes, many districts incurred new expenses, like technology. But they also saw other costs — operating buildings, running school buses, and paying substitute teachers — shrink. Jobs in public education dropped by 6% between March and April, as districts laid off or furloughed employees after buildings shut down.

There aren’t national estimates of the amount of money schools saved. One analysis of the budgets of four large (anonymous) school districts found that all had saved money by moving to remote instruction.

Total savings ranged from 0.7% to 2.3% of their annual budgets. For the average district, that would amount to $90 to $300 per student. Districts that continue remote instruction could see those savings continue, too.