Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

Give a girl a drone, and she might see her future as a scientist.

But if her teacher doesn’t have the training or resources to turn cool tech into lessons that stick, she’s likely to crash it, get frustrated, and move on.

Take Flight, a research project backed by $1.5 million from the U.S. National Science Foundation, aimed to solve that problem with a drone-focused curriculum for rural middle schools. The drones could fly in classrooms — no big outdoor space needed. The lessons were developed with teachers and easy for newbies to pick up. And the program placed a particular emphasis on girls, who often get frustrated by the handheld controller while their male classmates, who tend to have more video game experience, whiz by.

The lessons included real-world scenarios for using drones, like finding a lost child, that often appeal to young girls, and writing exercises to remind kids of what they’re good at before they try something hard.

At first, Laurie Prewandowski wrinkled her nose at Take Flight’s approach. It seemed “touchy feely” to the digital learning specialist who works in a rural New Hampshire middle school and is known as the “drone lady.” But then she saw kids enjoying the lessons and getting a STEM confidence boost.

“All those little things matter,” she said. “It’s really for any kid with a barrier.”

For decades, the federal government believed getting more students interested in science, math, and technology was a national security priority. But in April, the Trump administration cancelled funding for Take Flight and over 800 other STEM education projects funded by the National Science Foundation. The agency said it primarily terminated grants related to diversity, equity, and inclusion, as well as environmental justice and combatting disinformation.

It’s yet another way the Trump administration has sought to undermine efforts specifically meant to help women and girls and students of color. The administration has frequently claimed this work is, in fact, discriminatory, and has sought to withhold funding from schools that don’t comply with its civil rights vision, although that attempt is on hold for now.

Sixteen states sued to stop Trump’s NSF cuts, which represent a significant hit for STEM education research. NSF has long been a primary funder of this work, and one of the few institutions that helps researchers not only test new ideas in the classroom, but figure out what worked and why — which is key to replicating a successful program.

Researchers say these cancelled projects have broken trust, won’t be easy to revive, and left lots of data unanalyzed.

At the time Take Flight lost its National Science Foundation grant, its curriculum was being tested by 1,200 students and 30 rural middle school teachers across 10 states.

The research team had promising early data showing the program helped both boys and girls who weren’t interested in science or math before to envision working in a STEM field, said Amanda Bastoni, the lead researcher on the project.

That matters because rural students are less likely to go into STEM fields. They often attend under-funded schools and have less access to high-tech industries than their peers in urban schools. But now researchers won’t be able to follow up with kids to see if Take Flight altered their trajectory in high school.

“The government spent all this money but didn’t get the results,” said Bastoni, who is the director of career technical and adult education at the nonprofit CAST. Without funding, her team has to “turn in a final report that says: We have no idea if this really works or not.”

Why the government funds STEM education research

President Harry S. Truman signed the law that created the National Science Foundation in 1950, in part to recognize the key role scientific research played in World War II.

Congress has held that the agency’s support of STEM education and research are essential to the nation’s security, economy, and health. And, for decades, federal lawmakers have charged NSF with getting more people who are underrepresented in STEM into that pipeline to maintain a competitive workforce.

For example, a 1980 law calls for NSF to fund a “comprehensive and continuing program to increase substantially the contribution and advancement of women and minorities” in science and technology.

The law authorized NSF to create fellowships for women, minority recruitment programs, and K-12 programs to boost interest in STEM among girls.

The Trump administration’s approach runs counter to that. On April 18, the head of the NSF announced that any efforts by the agency to broaden participation in STEM “must aim to create opportunities for all Americans everywhere” and “should not preference some groups at the expense of others, or directly/indirectly exclude individuals or groups.”

Sixteen attorneys general, led by Letitia James of New York, are suing NSF to end that policy, arguing it does exactly the opposite of what Congress asked the agency to do. NSF has yet to file a response in court and a spokesperson for the agency declined to comment on the lawsuit.

It’s still unclear exactly how the Trump administration determined which grants to terminate.

In February, the Washington Post reported that NSF staff were told to comb through active research grants for keywords like “cultural relevance,” “diverse backgrounds” and “women” to see if they violated Trump’s executive orders. Some projects previously appeared on a list of “woke DEI grants at NSF” circulated by Sen. Ted Cruz, the Republican chair of the Senate science committee.

According to emails shared with Chalkbeat, Jamie French, a budget official with NSF, told researchers who lost their funding that their work no longer aligned with NSF priorities, but did not give more details. French told researchers the decision was final and they could not appeal.

In response to questions from Chalkbeat about why NSF cancelled Take Flight and other research projects, a spokesperson for NSF reiterated that rationale, and said the agency would still fund projects that “promote the progress of science, advance the national health, prosperity and welfare and secure the national defense.”

For Frances Harper, an assistant professor of mathematics education at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, the change was jarring.

She received a $700,000 grant from NSF in 2021 to work with 10 Black and Latina mothers with children in Knox County Schools. Together, they were studying how parents can advocate for improvements in their children’s math education and what teachers can learn from them.

Some of the Latina mothers in the study, for example, saw that English learners had a lot of anxiety about taking high-stakes tests, so they created a peer study group for them.

When Sethuraman Panchanathan, the NSF director selected during Trump’s first term who also served under President Joe Biden, visited her university in 2023, Harper said, “he asked me to convey to the mothers how much he valued families being involved in NSF projects.”

But after Harper’s research appeared on Cruz’s “woke” list, her university asked her to pause her work. She lost her funding the same day NSF announced changes to its priorities. And Panchanathan resigned a few days later.

NSF cuts felt from elementary school to college

Some researchers are applying for emergency funding from private foundations to salvage what they can. But much of their planned work will no longer be possible.

The Chicago Children’s Museum was working with Latino families from McAuliffe Elementary School in Chicago on a program known as Somos Ingenieros, or We Are Engineers, to get kids interested in engineering early on.

The team ran two after-school programs for around 20 families, but now won’t have funding to reach dozens more, or to reach the museum and wider school community.

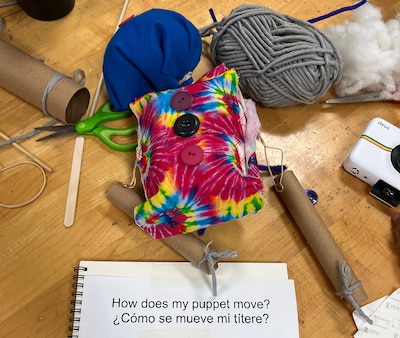

Parents and children met after school for six weeks to learn about building with various materials, including everyday items like sticks, pine cones, and rocks. That helped kids see engineering in their daily lives and it invited immigrant parents who played with those materials as kids to share their own experiences.

Families also got to put their building skills to the test. One group chose to create puppets and had to figure out how to get the intricate pieces to move correctly. Another picked piñatas and had to strategize how to make them hold heavy candy and survive lots of whacks.

Already, the research team was seeing evidence that the program had boosted parents’ confidence to do engineering activities with their children, said Kim Koin, the director of art and tinkering studios at the Chicago Children’s Museum, who was also the lead researcher on the project.

For Ryan Belville, the principal of McAuliffe, the loss of the program means his students will have fewer opportunities to imagine a college or career pathway in STEM and the arts.

“It may be that moment that they made that puppet that makes them want to be an engineer or a scientist,” Belville said.

And for Karletta Chief, much of the harm is in the lost talent and broken trust caused by the abrupt NSF cancellation.

Chief, a professor of environmental science at the University of Arizona, was a lead researcher with the Native FEWS Alliance, which received $10 million from NSF to address food, energy, and water crises in Indigenous communities, and to develop pathways for Native Americans and other underrepresented students to pursue environmental careers.

The Alliance had built a vast network of research and mentorship opportunities over six years, Chief said. It was involved in dozens of projects across the U.S., from creating K-12 school curriculum to mentoring Native students as they transitioned from tribal colleges to four-year universities.

“Our partnerships are built on trust and long commitment,” Chief said. “These are relationships that we have built over years, and it was just really unfortunate that we had to say, ‘sorry!’”

Now Chief and others are scrambling to find funding to cover graduate student researchers’ outstanding tuition and health care bills.

She worries even if the cuts were somehow reversed, it would be difficult to put the project back together. Many of the students and staff they had to let go have already taken other jobs.

“There’s a lot of knowledge and expertise that will be lost,” she said. “We were stopped when we were going full force. … Now we just went to zero.”

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.