Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

U.S. students are doing slightly better in math, and test score gaps that widened in the aftermath of the pandemic are narrowing, according to new data from testing organization NWEA.

But reading scores remain stubbornly stagnant, reflecting a concerning trend on other major national tests.

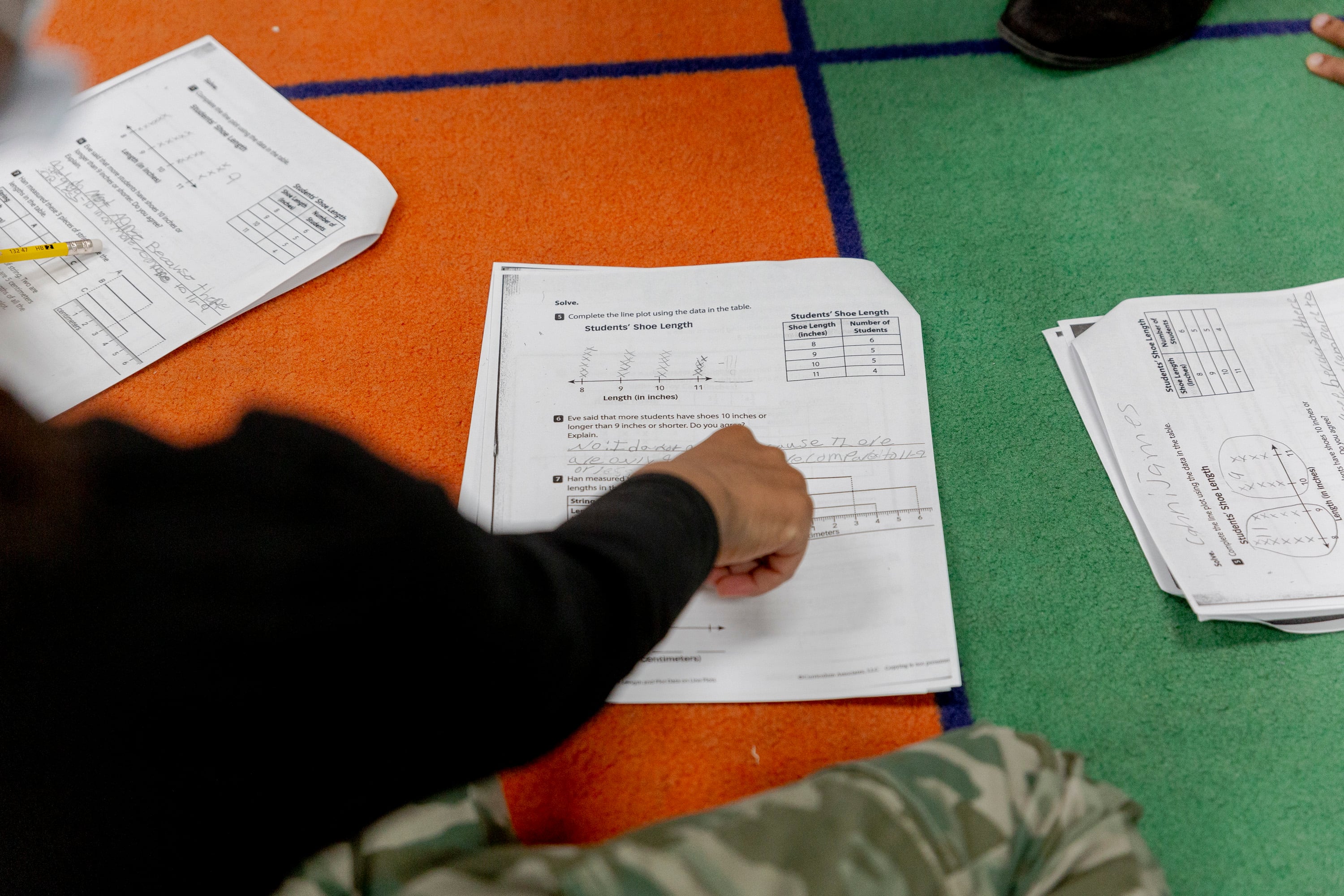

The data released Tuesday comes from MAP Growth Assessments given three times a year to more than 7 million students in grades three through eight in 20,000 schools.

These students attend schools that choose to give the MAP test, while students who take the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, reflect a statistically representative sample. The MAP data comes from the 2024-25 school year, while the most recent NAEP results come from spring 2024. NWEA weighted the results for students from certain subgroups to ensure the results were more representative.

The results add to our understanding of student academic progress — or lack thereof — in the wake of COVID disruptions and other societal changes, such as the increase in children using tablets and cellphones.

In math, student performance has steadily improved since the low point of 2021, though most students are still performing below their pre-pandemic counterparts.

Gaps in math test scores based on race and ethnicity as well as household income remain large but appear to be narrowing. For example, the gap between students at high-poverty schools and the national average in third-grade math shrank by about a third from spring 2021 to spring 2025. The gap for Hispanic students in third-grade math shrunk by about 41%, while the gap for Black students was about 27% smaller.

In each case, students in those groups made more progress than students in other groups instead of the gaps narrowing because some students did worse.

In reading, scores remained near their low points in 2021 for all groups and for most grade levels. Only eighth graders showed slight improvement from the previous school year.

In the immediate aftermath of school closures, math scores took a bigger hit than reading, but in the years since, math has shown improvement, while reading scores have remained stagnant or on some tests even declined further.

Researchers aren’t entirely sure why. Math learning may be more responsive to classroom intervention, while reading recovery may be hampered by trends outside the classroom, including the effects of technology on attention.

Gaps between high- and low-performing students started to widen before the pandemic, but COVID disruptions appear to have accelerated the trend. Recovery has been slow, with data from other assessments showing even students who weren’t in school yet during COVID closures struggling.

Third-grade students who took MAP tests last year entered kindergarten in fall 2021.

Karyn Lewis, vice president of research and policy partnerships at NWEA, said the results reflect “something systemic about education has changed.”

“This speaks to the lingering impacts, the shock to the system as a whole,” she said.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect the correct year that last year’s third graders entered kindergarten.

Erica Meltzer is Chalkbeat’s national editor based in Colorado. Contact Erica atemeltzer@chalkbeat.org.