There’s little debate among teachers that class size matters.

One survey found that nine in 10 teachers said that smaller classes would strongly boost student learning.

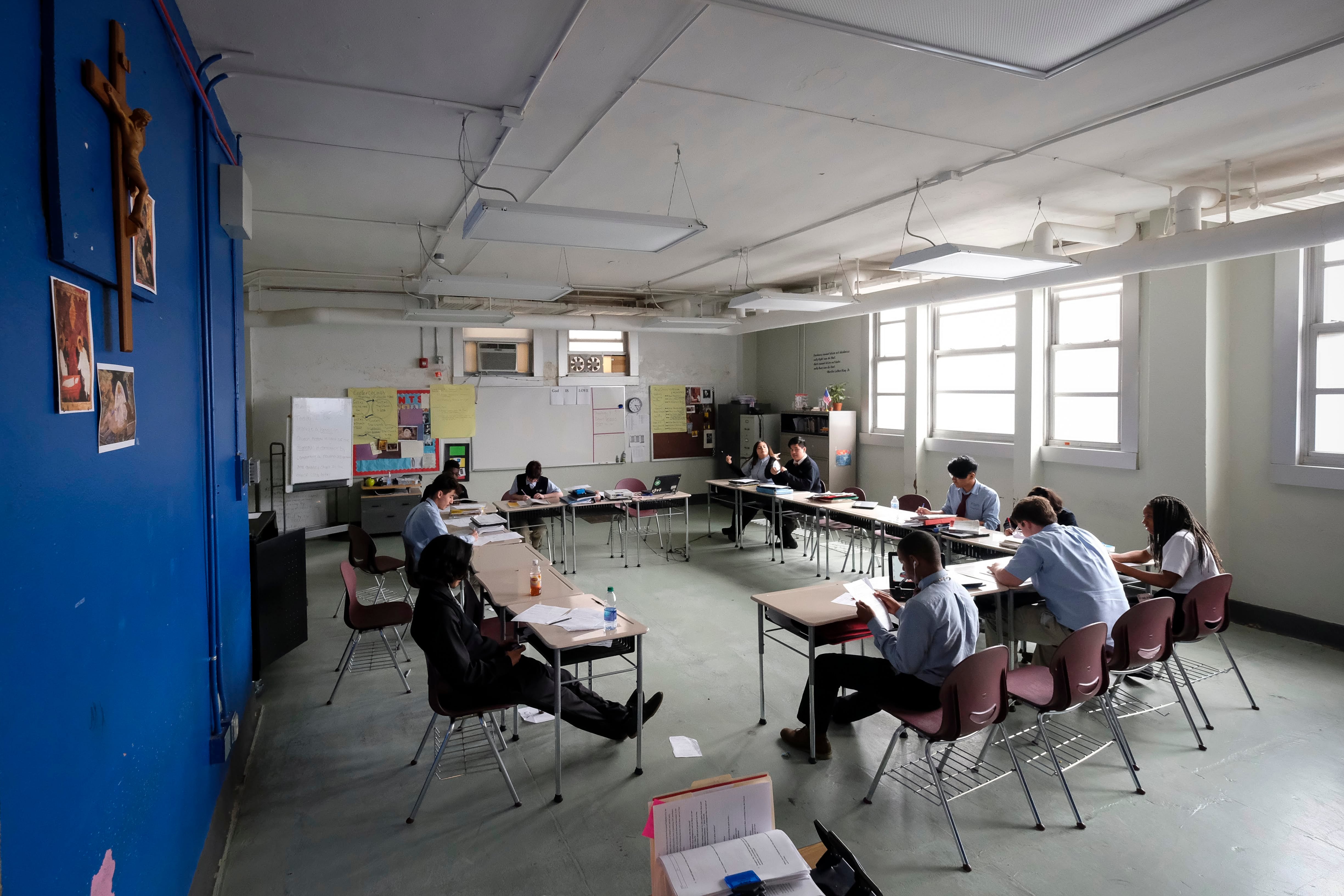

“Huge class sizes are a challenge because it makes it hard to focus on individual students who are struggling or who are ready to go on to the next level,” one high school teacher explained.

But some education policymakers and pundits remain skeptical, arguing that reducing class sizes is of limited value and diverts money from more effective investments.

This long-running debate is back in the news as New York City, the country’s largest school district, will likely be required by state lawmakers to set new caps on class sizes. It’s also likely that schools across the country are undergoing a quiet experiment in class size reduction, as enrollment has dropped while the number of teachers employed has barely changed.

So does class size matter? And is it really the best use of finite educational dollars?

Chalkbeat revisited the research on these questions. The key takeaways: Students often do better in smaller classes. But there’s no agreement on exactly how much better, and it remains an open question whether or not class size reduction is a particularly good use of funds that could go elsewhere.

All told, “the impact of smaller classes would depend on many factors,” said Northwestern University economist Diane Schanzenbach, “including whether funds are reduced for other student supports, the quality of the newly hired teachers needed to staff the smaller classes, and adequate availability of classroom space.”

Smaller does seem better when it comes to class size

The most famous and rigorous study of class size reduction took place in Tennessee beginning in 1985, when some kindergarten students were randomly assigned to unusually small classes through third grade. Test scores in the classes of 13 to 17 students quickly surpassed scores in the larger classes of 22 to 25. Those gains persisted for years.

Other studies in California, Minnesota, New York City, North Carolina, Texas, and Wisconsin have shown lower class sizes boost test scores, too.

A few studies have also found other benefits, with smaller classes leading to greater classroom engagement and higher attendance. In Tennessee, researchers later found that students in smaller classes in early grades were also more likely to attend and graduate from college.

It’s not clear how big those benefits are, though

These studies do not agree on how much improvement schools can expect from smaller class sizes. In some research, the impact of small classes is more modest than the large gains seen in Tennessee. In Minnesota, for instance, 10 fewer kids in class translated into a tiny increase in test scores.

There are also a few instances where smaller classes didn’t seem to improve test scores at all, including in studies in Connecticut and Florida.

“Most studies find at least some evidence of positive effects of smaller classes, but the size of these benefits is inconsistent,” wrote Urban Institute researcher Matt Chingos.

Smaller classes mean hiring lots of teachers, which is complicated

Substantially reducing class size generally requires schools to go on a hiring binge in order to staff the new classes — and those new teachers are often less experienced and effective than their peers. That means the benefits from lower class size may be partially counteracted by reductions in teacher quality, which has been shown in studies from California and New York City.

In both those cases, the dip in teacher quality appeared temporary, though. In California, multiple studies have suggested lowering class sizes ultimately improved learning.

Overall, the changes “increased achievement in the early grades for all demographic groups,” one set of researchers wrote, finding no evidence of a long-lasting decline in teacher quality.

Lowering class sizes comes with tradeoffs

Some argue that putting resources into reducing class sizes — which requires more teachers and often additional classroom space — is misguided. Schools should focus on getting and keeping better teachers, not simply adding teachers, with the resources they have, they argue.

That comparison implies that there is a straightforward and less costly way to improve teacher quality, but it’s not clear that’s the case.

For instance, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and several school districts pumped $575 million into a teacher evaluation and quality effort several years ago. (Gates is a funder of Chalkbeat.) Researchers later found it had little if any impact on student outcomes. It may well have been more cost effective to use that money to reduce class sizes instead.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean that New York’s class size cap is the right approach. The state is poised to force the city to choose reducing class sizes over other potential investments, and research doesn’t strongly support this either.

Placing a hard cap on class sizes may also mean spending a lot to reduce class sizes in better-off schools, limiting the city’s ability to target resources to high-needs students.

Schanzenbach argues that removing the discretion of local officials is concerning. “In a well functioning system, principals and superintendents should be looking at their situation and figuring out, how are we going to best invest these resources to serve our kids,” she said.

There’s still more to learn about how class sizes affect kids, but the perspectives of teachers and parents should be taken seriously

In education policy circles, you’ll often hear confident claims about class size reduction: “It works best in early grades,” “It only works if class sizes are very small,” “It helps disadvantaged students most,” or, “It’s not cost effective.”

In general, the evidence for these claims is mixed, limited, or even non-existent. Remarkably, for instance, there is little rigorous evidence on how class size affects students in high school. Many of the studies are also quite dated.

In the meantime, many parents and teachers say class size makes a difference.

Michael Doerfler, an elementary teacher in Clark County’s virtual academy, has seen that even in his unusual setting. He loves teaching online, but this year he’s had a class load of over 40 students and struggled to give students as much individual attention as he’d like.

“The thing that would help the most would be the budget to have small classes — 41, 42 is a lot,” he said.

Matt Barnum is a national reporter covering education policy, politics, and research. Contact him at mbarnum@chalkbeat.org.