Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

Sonali Kohli has always liked young adult novels.

They’re fun to read. They don’t shy away from serious, or even traumatic, subjects. And they are deeply rooted in hope.

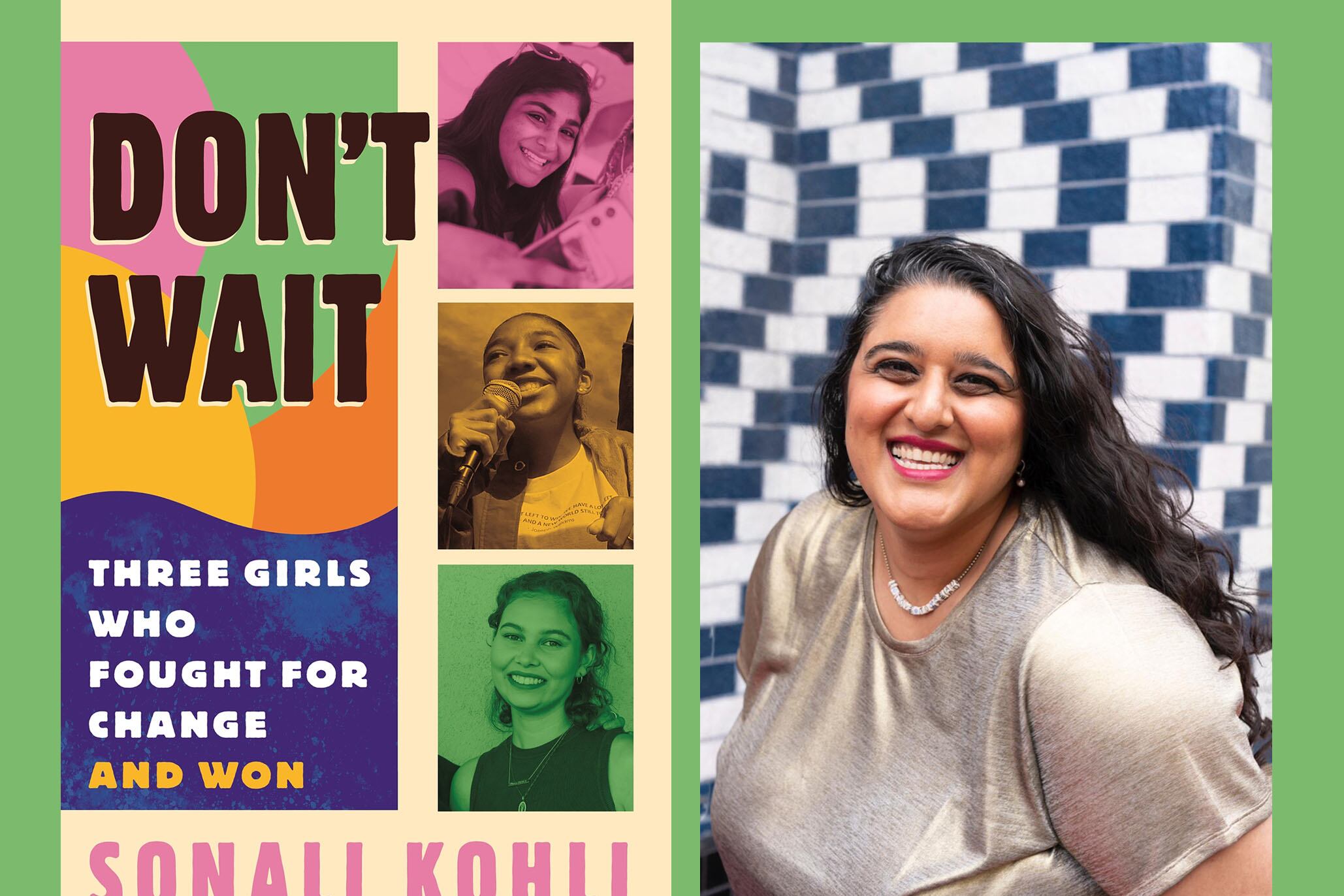

So when the California-based journalist set out to write “Don’t Wait,” her new nonfiction book out this week, she sought to capture that same sense of “realistic hope” as she shared the true stories of three young women of color fighting for change in America.

Each activist takes on an issue important to her life.

Nalleli Cobo protests the urban oil fields that sicken her and other kids in the Los Angeles neighborhood she grew up in. The campaign she launches with her mother, People Not Pozos, eventually helps shut down the oil well across from her childhood home.

When Kahlila Williams faints from dehydration at her school’s picnic, a school police officer asks if she’s having a drug overdose. The encounter spurs Williams to advocate for the removal of school police from Los Angeles Unified schools. Her work helps persuade the school board to cut the school police department’s budget and reinvest the money to hire counselors, school climate coaches, and other staff to support Black students.

Sonia Patel Banker, meanwhile, grows up in San Francisco with access to arts classes at school and private choir lessons. But when she finds out many California students don’t have access to arts education, despite a state law saying schools are supposed to provide that, she reaches out to the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California to work on their funding campaign. Her advocacy helps lead to a successful voter referendum that now requires the state to give schools extra funding for arts education.

Kohli hopes young people who read the book will be able to learn from the three girls and their different approaches to activism.

“I want people to just be able to say they learned something from it, and that it helped them engage in their community in any way — big or small,” Kohli said.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

“Don’t Wait” comes from a speech Kahlila gives to her school board. Why did you choose that as your title?

Part of writing for teens, and writing about these young women, is that I wanted to highlight their voices as much as possible. When I heard Kahlila say it at the school board meeting, I thought: This so deeply embodies what she did. She didn’t wait.

[For] adult activists, you work toward something your whole life and there are setbacks, and you keep going. But when you’re doing activism as a young person, or say in high school, you have four years, right? So there is an urgency.

It also embodies the book’s message to young people: You don’t have to wait until something horrible happens to you or someone you love. You don’t have to wait until you’re an adult. You have agency now. And if you want to effect change in your community, you can do that.

You talked with youth about what they wanted to see in a book like this. What did they share with you?

My audience was always very clear to me. I was writing to teenagers.

Some of it was: We want to see people from our community who are doing this work. [They also] wanted to see advice.

Kids wanted to know: How do you get involved in activism? If you want to change something at school, how do you do that? Is a petition around dress codes enough? What else can I do? What does activism look like? How do I know who to trust?

How did you land on the three movements you focused on in the book?

I wanted to focus on movements where the people who I was following were rooted in California, because that’s the state that I’m from.

Californians, especially Californians in the big liberal cities, see ourselves as these bastions of equity. The reality is inequity is absolutely present. And it’s insidious. So, in the place that we consider the most liberal, the most welcoming, where are the problems, and how are people fighting them here? And how can that be useful to other people around the country?

Defunding school police — that’s a movement that’s really relevant. Environmental justice was very important for me to include in the book, and environmental racism, more specifically, because a lot of the narratives we read and hear about environmental justice work tend to be focused on white folks. Arts education is something that people don’t think about as much when they think about activism, but the reality is, art is so vital to our lives.

It also depended on having a mix of young women who are doing this work, and who are doing different kinds of work, and had different paths to their work.

Sonia says she feels like arts education is being treated like a second-tier social justice issue. What did she want people to know about the value of arts education?

Where that comes up in the book is when it’s being left off of a petition, that is [called] “Counselors, Not Cops and Arts, Not Arrests.” And the ACLU attorney wants to take off the “Arts Not Arrests” part. But arts and arrests are really connected.

When you provide students more access to education outside of what is required of them, you offer students the option to develop passion, to explore different kinds of activities, to have a safe place to work, to feel joy, to express their emotions in a healthy way. I think giving that weight is important.

Think about how much we all turned to art, in all of its forms, during the pandemic. In our darkest times, art is vital. And it has great impacts for children to have access to it.

In the book, there’s a moment where Kahlila wonders: What do I do with this bullhorn? And there’s another moment where Sonia is like, should I just email the ACLU? Why was it important to include these moments where the girls are not sure how to get started?

A lot of the narratives we hear about youth activism are very savior-y. Every generation tells the generation below them — it happened to Gen Z, and now it’s going to happen to Gen Alpha — You’re the ones who are going to save us, I’m so excited for what you’re going to do. And it’s really not fair. Lionizing kids in this way also takes away their humanity.

Internal conflict and being a little bit unsure of how to proceed is a really relatable feeling. And it’s something that a lot of kids go through. I don’t like what’s happening around me. And I do want to do something, but like, I’m not Malala. I’m not a Parkland youth.

We hear a lot about the experiences of activists who have one huge catalytic event. And then they’re activists, and that’s it, and they’re going for it, they’re out in front of hundreds of thousands of people.

But the reality is, to get to that point there’s a lot of little things. There’s being nervous, there’s not knowing what to do with a bullhorn, there’s feeling awkward, there’s missing class. Hopefully, if somebody is reading this, and they’re like: I feel really awkward going to a protest, I don’t really know anyone, they can think about Kahlila and how she dealt with it.

Activism can be disruptive to the girls’ lives. Nalleli had to change schools. Kahlila has trouble sleeping. Why did you want to show some of the mental and physical challenges of activism, alongside their victories?

I wanted a book that’s rooted in hope, but also reality. There’s a lot that’s positive about how engaging in activism impacts you as a person [and] your mental health.

There are also moments where it can be really hard. And I wanted people to see that that is something that these girls experienced, and how they dealt with it. [That] it’s okay to take a break, it’s okay to step back. It’s okay for your activism to look different than other people’s based on what your needs are.

What role did school play in the girls’ activism?

For some of them, their activism was deeply rooted in their community [and] their school. Kahlila was trying to get police off of her campus. For some of them, it was about the home, and the home being safe. Part of Nalleli’s work also is about getting oil wells away from schools. Sonia sought out this work outside of her school, and realized that she had access to so much art, in and out of school, and others didn’t.

But I do think that school-based movement work is a very large part of student activism. Organizations like Students Deserve, which Kahlila is a part of, are deeply rooted in school and also in corrective data-gathering.

Before I started the book, I was covering [Los Angeles Unified School District] and there were reports from Students Deserve at a bunch of different schools of school police pepper spraying kids on and right off of campus. LA’s school police department is subject to public records laws. So we asked them to tell us how many instances they’d had of pepper spray in the last year [or so], and they told me none!

And I said: Okay, well, what about this day? I have a video. And this day, at this time? And that existed because [of] these students, who started their activism in their schools, and then met as a collective, [and] realized that this was happening at multiple places. And then, all of a sudden, [the school police department said]: Oh, yeah! Actually, we do have reports of that.

Each of the girls is a leader in her activism work. But they also turn to adults for support. What would be helpful for teachers, parents, and mentors to keep in mind about the different ways they can support young people in their activism?

These girls each have a question, or they have an experience, or they have a problem. And they seek out adults to support them. The support tends to be along the lines of: Here’s how you can find the information you need for yourself. And here are some things that people do to address these problems.

In Nalleli’s case, her mom is the most grassroots of organizers. Her mother and other mothers were calling authorities to come and get the air quality checked [where they lived] because their children were having extreme health effects [from a nearby oil-drilling site]. And then that became a passion for Nalleli, also, as a child, to speak up for herself.

I think that agency is really important, and creating scaffolding and support so that young people can have that agency.

[That can mean] arming kids with the skills to do their own research and fact-check, and not putting down their sources of information, but rather empowering them to get more.

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.