Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to keep up with education news from Denver and around the state.

The Sheridan school district has no superintendent this month — and no clear plan to open a search.

Some board members want to appoint the internal candidate recommended by the departing superintendent, Pat Sandos. That proposal has divided the board, with one member accusing the board president of trying to bribe her to go along.

Meanwhile, the board has agreed to pay Sandos his full salary for a transition year starting in July, even though he’s officially retired as of May 31. Community members have launched a petition to terminate Sandos’ extension. For too long, they say, the district has overlooked and ignored the needs of parents and students, and it’s time for new leadership.

The district on Denver’s southwest edge serves about 1,100 students, including a large percentage from low-income families or identified as homeless. Like many in the metro area, the district is struggling with declining enrollment, which means less revenue and tighter budgets. The teachers union is seeking raises similar to those neighboring districts have agreed to, but negotiations have stalled. Meanwhile, teachers and parents alike report high turnover and important positions sitting vacant.

Alejandra Balderrama, a Sheridan parent, got involved in the petition requesting the current superintendent leave sooner because she’s concerned about staff turnover, especially the sudden departure of the elementary school principal after the school was recognized for students’ exceptional academic growth.

“I really don’t find that to be fair,” Balderrama said.

She said she hopes a new leader will mean more stability among staff and better communication with parents.

“I would like constant communication between not only the teachers and principals or administration, but also with the parents,” Balderrama said. “It’s important for us to really be involved.”

Board split on how to search for a superintendent

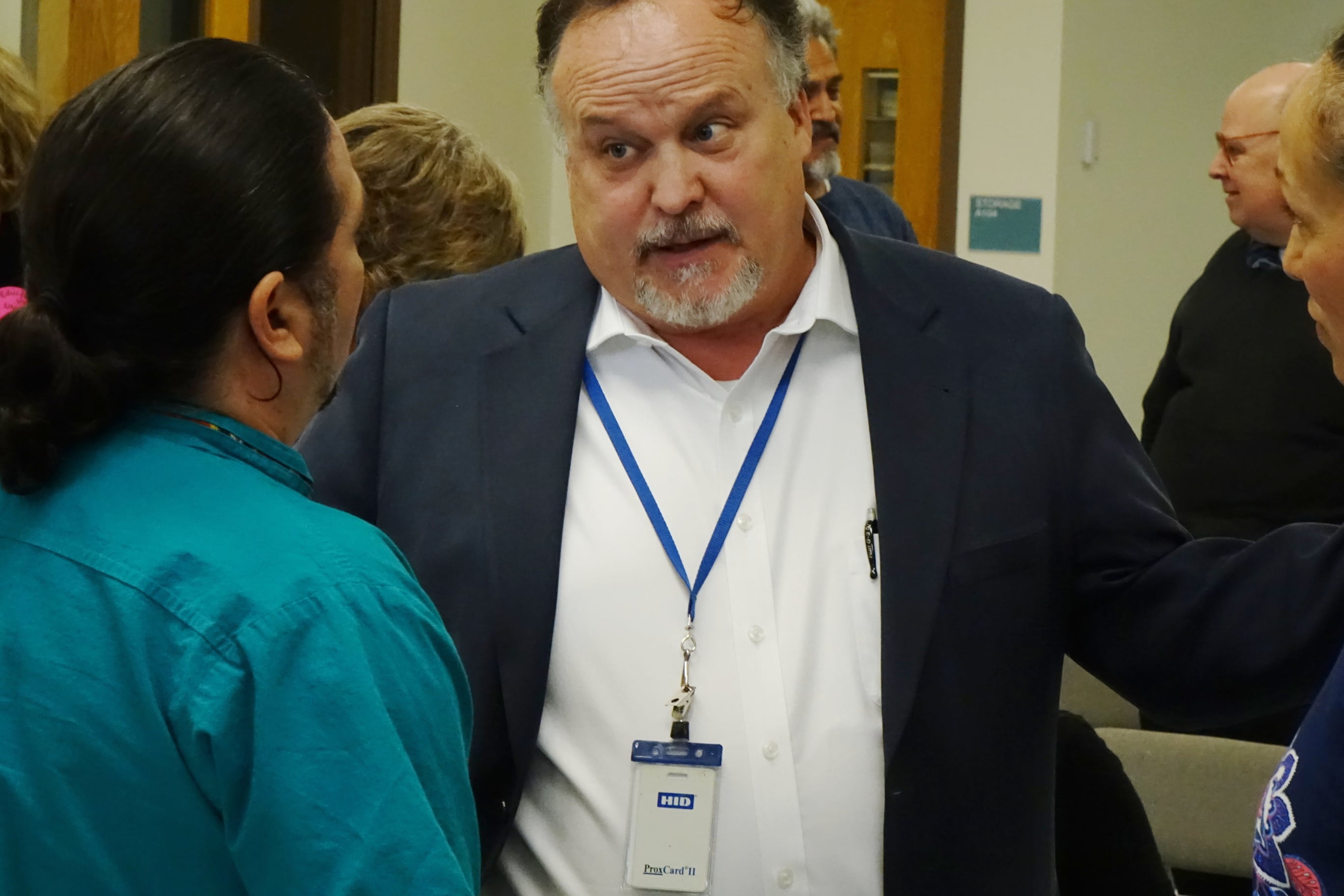

Superintendent Pat Sandos was hired in 2018 amid pushback from community members who preferred one of the other finalists — a Hispanic educator from southwest Denver. Instead, Sandos, an internal candidate, was selected in a split vote.

At the time, board member Daniel Stange said the district needed someone from outside to listen to the community’s calls for change.

This time, Stange, now the board president, believes that there is no need to spend thousands of dollars on a superintendent search firm if there’s a good internal candidate.

“They turn out the same type of superintendent, filtering the way they do, and you get what you get,” Stange said. “If we want a different result, a new type of superintendent, then why would we be spending money to hire a search firm?”

“Our internal search is really focused on the culture of our schools,” Stange added. “We want a bilingual female. The majority of the board is supportive of an internal candidate that matches that.”

But veteran board member Sally Daigle, who voted for Sandos in 2018, feels strongly that the board needs to do a comprehensive search. The disagreement began at the same December meeting when Sandos announced his retirement.

Sandos recommended the board appoint his chief academic officer, Veronica Maes, to be his replacement. He would train her during his transition year.

Daigle advocated for the district to hire the Colorado Association of School Boards, of which she is an active member, to lead a search. The push to consider only one internal candidate concerns her.

“There’s something just not right about the whole thing,” Daigle said. “I would not argue for an hour and a half that we needed to do this if I didn’t think so.”

At a tense board meeting this spring that sometimes turned into shouting, Daigle read text messages from Stange that she later described as an effort to bribe her into agreeing with the plan using reimbursement payments as leverage. Sheridan is one of a few Colorado school districts that pays board members, allowing reimbursement for certain meetings and costs.

“I told you I would approve the costs for you to work with CASB if you didn’t give us a lot of pushback with this issue,” reads the text message from Stange, which Daigle shared with Chalkbeat. “It really feels like you are trying to push us into a costly and lengthy process? I hope you remember that we are a 5 member board. Majority rules but consensus will always provide a confident image to our constituents.”

“It was threatening, coercion, or whatever you want to call it. I was kind of pissed,” Daigle said.

Daigle serves on a CASB committee that requires monthly meetings and is a full-time caretaker for her mom. She wants to get compensated when she does work that requires her to make other care arrangements for her mom.

Stange said it wasn’t meant as a bribe or coercion, but said he knows that “to some people it might sound like that.”

Stange said he was upset that Daigle was “making a fuss” about the superintendent search and said there was disagreement over whether Daigle’s CASB conference work should count as school board work.

According to a records request, as of May 21, only two board members have received any payment since the policy took effect. Daigle received $1,725, and Maria Delgado-Garcia received $1,093.

Internal candidate says her passion is in working to close equity gaps

Maes, who joined Sheridan as chief academic officer last year, said she wants to be superintendent to keep working on important projects.

“My entire life, my passion is closing equity gaps, working with multilingual learners — that is my why,” Maes said. “I was a Spanish-only speaking child, and I did not go through a great sink-or-swim experience. When I moved over to Sheridan last school year, it really was filling my bucket.”

“When Pat announced he was going to retire, it concerned me for the work,” she said. “We are getting a lot of traction.”

Stange said he’s happy to hire Maes into the top district role — lauding her approach to equity and the fact that she’s a Hispanic woman.

Maes has agreed not to request a higher salary during the transition year so that the small district will pay only one superintendent salary — to Sandos. Sandos, meanwhile, said he considers himself to still be the superintendent.

Daigle said a broader search would ensure the district finds the best candidate. And if that is Maes, she will still stand out even more, Daigle said.

The board could vote to appoint Maes as soon as this month. That’s when the board expects a report on community feedback on the district’s goals and direction, based on a survey and some meetings. If Maes agrees with the community priorities, it makes sense to appoint her, Stange said.

Daigle is frustrated because the district has paid a pair of consultants $12,000, twice what CASB would have charged to conduct a superintendent search that included community engagement. Stange said the consultant contracts include work on a strategic plan, and the community feedback also will support that work.

While parents agree with the board president that representation matters in a leader, some worry that any internal candidate, Hispanic or not, might continue to ignore their requests.

Alexis Marquez, a leader of the advocacy group Sheridan Rising, said that last year, Sheridan parents presented a list of requests to the district — including that the district provide Spanish interpreters for school board meetings so more parents could participate.

“It wasn’t a hard ask, but this letter went completely ignored. It was never even acknowledged,” Marquez said. “This is just a blatant disregard for the community. If you can’t speak the language, you can’t partake.”

Sandos said he would like to add interpreters to school board meetings but logistics and cost have been a challenge. Other school districts with large numbers of Spanish-speaking families, such as Adams 14, have offered interpretation for years.

Maes said she wasn’t aware of the letter or the request. She has ensured that schools offer interpreters for meetings with parents, she said. It wasn’t something she had considered for school board meetings.

Maes said better communication with the community would be a top priority if she’s chosen as superintendent, along with recruitment of new students and teachers.

“I just want to do the work,” she said. “This kind of stuff gets in the way of that.”

Yesenia Robles is a reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado covering K-12 school districts and multilingual education. Contact Yesenia at yrobles@chalkbeat.org.