This is republished as part of a series in collaboration with the Headway Election Challenge. Chalkbeat and Headway at The New York Times will ask young people to share their insights and perspectives throughout the 2024 presidential election.

Early in 2024, the Headway team, along with Chalkbeat, a nonprofit news organization focused on education in America, started talking with high school students about the upcoming presidential election. We wanted to understand how youth were processing an election in which age had become an issue, especially four years after young people turned out at among the highest levels since 18-year-olds received the right to vote.

In September, we started the Headway Teen Election Challenge, posing questions to teenagers across the United States. So far, we’ve heard from more than 500 teenagers in 37 states and Washington, D.C.

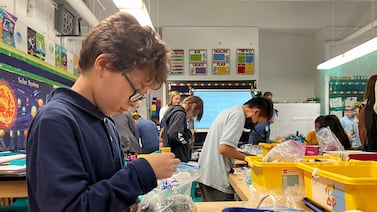

Most of our respondents have been individuals, but we’ve also received submissions from entire classes in cities like St. Louis, Philadelphia, and New York City. We’ve heard from many teenagers who are starting to shape our political system in ways that go well beyond voting.

In every questionnaire we’ve sent to students, we’ve asked for questions too, and we’ve compiled the most frequently asked here, along with pointers to relevant reporting from The New York Times.

Here are some of the main themes we’ve heard so far.

Most participants expect the election to have a major or moderate impact on their lives.

The election isn’t a distant concern to most of the teenagers we’ve heard from so far. Well over half of our respondents say they expect to feel the effects of the outcome in their lives or in their families’ lives.

The reasons they cite are not unfamiliar. The impact on the economy, immigration, and abortion policy were all frequently mentioned. And unsurprisingly, the teenagers who described themselves as the most attentive to the election were also likely to expect it to affect them most.

Many teenagers mentioned class. Some respondents who said they expected the election to have a minimal impact on them cited their family’s wealth as a reason, and some who expected significant effects wrote that they came from a lower-income or a working-class background.

In a word, students and teens find the election “interesting.”

Asked to describe the election in a single word, “interesting” was the top response. “Chaotic” (or “chaos”) was the next most common description, followed by “confusing” and “informative,” which were tied in our unscientific sample.

When we asked teenagers how they were informing themselves and others about the election, we expected them to say that social media played a big role. And for some, it does. But most said it only slightly or moderately affected their views.

Most respondents said they were very or mostly comfortable talking about the election with peers and classmates. Some said they and their peers shared a bubble in which conflict over politics was relatively rare.

But many teenagers mentioned challenges in discussing the election with family members and in the classroom, even while they often described parents and teachers as key influences on their politics. This squares with what we’ve heard from teachers, many of whom express deep reluctance in broaching political subjects in the classroom, as things like book selections have become more deeply politicized.

A surprising number of participants mentioned Project 2025.

Mentions of Project 2025, a set of sweeping conservative policy proposals compiled by the Heritage Foundation, were surprisingly frequent among the responses to our questionnaires. In fact, “2025” ranked higher among the words respondents used to describe the potential impact of the election than “Trump,” “Harris,” “economy” or any particular issue.

Even when we convened groups of high school students in person at The Times’ headquarters, Project 2025 came up without prompting, and most in attendance were at least somewhat familiar with it.

Many young people feel they can make a difference in the election, even if they can’t vote.

Young people face constant skepticism of their role in electoral politics. Many teenagers and adults alike downplay the idea that there’s any reason for people who haven’t yet reached voting age to pay attention to the messy, complicated politics of the United States.

Most of the youth we’ve heard from cannot vote this year. But they and their peers have been central to some of the most contentious subjects relating to the election, such as abortion, gun violence, and campus protests. And some have realized they can have an impact on the issues that matter to them beyond voting, even if they can’t vote themselves.

These teenagers are registering eligible voters and participating in protests. Many have said they pay as much or more attention to downballot races as they do to the presidential ticket. Ayaan Moledina, a sophomore in high school, is responsible for legislation that has passed the Texas House of Representatives.

We were especially interested in what motivated these highly politically engaged teenagers, and, in interviews, several shared a few common traits. They had supportive and inspirational adults in their lives encouraging them to use their voice. They had access to enough resources — whether rides to events or a stable internet connection — that allowed them to participate in ways some youth could not. And their growing sense of history has begun to teach them that rising generations can sometimes force change in a way their elders cannot.

For Ayaan, 15, the awakening started in a discussion in a fourth grade classroom focused on the threat of a school shooting — an experience he realized few adults have faced.

“I still get told to this day that, you know, oh, be a kid, go play some video games, go play some sports,” he said. “There are so many issues that affect us that it’s just not possible to leave it to the adults, because to be quite frank, the adults are screwing it up a lot. When you’re talking about things that affect us, then you better include us. Because we’re the ones living it.”

Are you a teenager? Tell us your thoughts!

If you are between 14 and 19, we would love to hear your thoughts. (And if you’re not, but know someone who is, feel free to send them this; it’s not behind The New York Times’ paywall.) Does what we’ve heard resonate with you? Have you had a different experience? Let us know.

Headway’s Teen Election Challenge will continue until the election. Over the next few weeks, we will continue posing questions to teenagers, and gathering moments to remember for a time capsule of the 2024 election.